Over the Christmas holidays, many will be planning their holiday journeys and turning to Google maps or their Satnavs to check their routes. Nowadays, roads are an integral part of any map but the historical challenges of travel and transport meant that roads were rarely shown on earlier printed maps until the 18th century.

Since the earliest times people have migrated and traded around the world but weather conditions and physical geography have meant that routes were rarely as fixed as today. In Britain, travel in the winter was near impossible on anything other than major routes with reasonable man-made surfaces of stone or those, like the ancient drovers' routes, that followed upland paths across free-draining ground. The carefully constructed Roman roads that had enabled troops and merchants to move quickly across the Empire had fallen into almost total disrepair by the Middle Ages, and those in Britain were reputedly among the worst in Europe. Often, the only 'roads' were narrow winding lanes or bridle tracks between cultivated fields and, in the absence of hedges and fences, they frequently changed course as weather conditions or changes in land ownership dictated. Where navigable, river routes were often favoured. Travellers frequently preferred to travel along the coast by sea which was longer but often more reliable and faster, winds permitting.

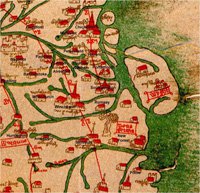

One of the earliest maps to show roads was the 'Gough' map of Great Britain of circa 1360 (named after its 18th century discoverer) where major routes are shown diagrammatically in red. There is evidence that copies of it were still being used some 200 years later. In the earliest printed county maps by Saxton and Speed, roads were omitted which suggests that, for the surveyors, they were not substantial or permanent enough to be noted. However, rivers were depicted and it is now thought they played an important part in the surveying process as points from which to calculate traverse measurements.

One of the earliest maps to show roads was the 'Gough' map of Great Britain of circa 1360 (named after its 18th century discoverer) where major routes are shown diagrammatically in red. There is evidence that copies of it were still being used some 200 years later. In the earliest printed county maps by Saxton and Speed, roads were omitted which suggests that, for the surveyors, they were not substantial or permanent enough to be noted. However, rivers were depicted and it is now thought they played an important part in the surveying process as points from which to calculate traverse measurements.

So how did these early English travellers manage to find their way? By the 16th century, 'road books' were becoming popular. These usually consisted of brief descriptions of the countryside through which roads passed and, of more importance, details of the main 'high Wais' with distances between stopping-places. The earliest was the "Itinerary" of John Leland written about 1535 to 1545, followed by a number of others published in the last quarter of the century. These include Holinshed's "Chronicles of England, Scotland and Ireland", first printed in 1577, which contained tables of roads and distances, frequently copied by other publishers.

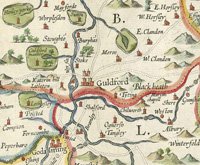

In England it was left to Saxton's contemporaries, John Norden (1593 to 1598) and William Smith (1602), to be the first to show roads (using a double-dotted line) on a few county maps. These include a rare example of Surrey engraved by Charles Whitwell and only discovered in the early 20th century. Their example was not followed by the engraver William Kip who created the maps for Camden's Britannia or by John Speed in his atlases. As their works dominated the market for many years, roads were still only rarely shown.

From about 1668, sheet maps showing post roads and 'cross-roads' in England and Wales appeared, and gazetteers of cities and market towns complete with distance tables were published. For practical purposes, there were obvious limitations to the amount of detail which could be included on sheet maps, and it was not until the invention of the 'strip map' by John Ogilby that practical travellers' maps appeared.

From about 1668, sheet maps showing post roads and 'cross-roads' in England and Wales appeared, and gazetteers of cities and market towns complete with distance tables were published. For practical purposes, there were obvious limitations to the amount of detail which could be included on sheet maps, and it was not until the invention of the 'strip map' by John Ogilby that practical travellers' maps appeared.

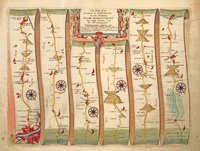

In 1675, Ogilby published to 'Great Applause' the "Britannia - a Geographical and Historical Description of the Principal Roads thereof", comprising 100 maps of the most important roads of England and Wales. Engraved in strip form, the maps gave details of the roads themselves and descriptions of the country on either side, each strip having a compass rose to indicate changes of direction. In his advertisement, Ogilby's survey was said to have measured over 25,000 miles of road (in fact, the maps covered 7,500 miles), all surveyed on foot with a 'perambulator' or measuring wheel to log the distances from place to place. He used the standard mile of 1,760 yards, introduced by statute in 1593, but which had never replaced the old long, middle and short miles, an endless source of confusion to travellers. Their immediate popularity was shown by four issues of the Britannia in 1675 to 1676 and a reprint in 1698.

Ogilby's maps primarily indicated the post roads of England and Wales. There had been a system of Royal Posts in use since the time of Edward I and, in 1660 a 'Letter Office of England and Scotland' was established for public mail and a distribution network using the post roads soon became widely used.

Ogilby's maps, and those which soon followed, met a great and growing need. From 1676 onwards many more (but not all) county maps included roads. However, on the Senex map of 1729, minor roads leading off from the post roads were left incomplete as on the strip maps. It was only when Turnpike Trusts were set up to raise funds to offset the costs of road improvements that there were real improvements for travellers. As travel became easier and more comfortable, so the number of journeys taken rose, with a consequent demand for road books and atlases which were published in ever increasing quantities and sizes, but particularly in convenient pocket size volumes. Among the most popular works in the early 18th century were those by John Senex and Emanuel Bowen, followed by Daniel Paterson, William Faden and, at the end of the century, by John Cary, the most popular of all.

Ogilby's maps, and those which soon followed, met a great and growing need. From 1676 onwards many more (but not all) county maps included roads. However, on the Senex map of 1729, minor roads leading off from the post roads were left incomplete as on the strip maps. It was only when Turnpike Trusts were set up to raise funds to offset the costs of road improvements that there were real improvements for travellers. As travel became easier and more comfortable, so the number of journeys taken rose, with a consequent demand for road books and atlases which were published in ever increasing quantities and sizes, but particularly in convenient pocket size volumes. Among the most popular works in the early 18th century were those by John Senex and Emanuel Bowen, followed by Daniel Paterson, William Faden and, at the end of the century, by John Cary, the most popular of all.

Examples in the Local Studies collection at Surrey History Centre

- "A new and accurate description of all the direct and principal cross roads in Great Britain" by Daniel Paterson, (1778), reference 388.1 S1x

- "Cary's new map of England and Wales with part of Scotland: on which are carefully laid down all the direct and principal cross roads, the course of the rivers and navigable canals" by John Cary, (J Cary, 1816), reference 912 S1x

- "Surriae Comitatus Continens in Seoppida mercatoria vii Ecclesias parochiates cxl" by William Smith, engraved by Joducus Hondius circa 1602 (J. Overton and P. Stent, 1665), reference M/150

- "Road from London to Portsmouth in com: Southamp: actually surveyed and delineated" by John Ogilby. circa 1675, reference M/465

- [The roads through England delineated or, Ogilby's survey, revised, improved and reduced to a size portable for the pocket], engraved by John Senex, (John Bowles, circa 1757), reference M/841

See also

- An Eighteenth Century Map of Surrey

- The men behind the making of a map

- John Norden's Mirror of Britain

- Old Surrey county maps

Images

Select image to view a larger version.

- Portion of the 'Gough' map, showing south-east England including Surrey

- Portion of "Surriae Comitatus Continens in Seoppida mercatoria vii Ecclesias parochiates cxl" by William Smith, engraved by Joducus Hondius circa 1602 (J. Overton and P. Stent, 1665) (reference M/150)

- Road from London to Portsmouth in com: Southamp: actually surveyed and delineated by John Ogilby. circa 1675 (reference M/465)