Introduction

The focus of this document is to highlight to individuals and organisations involved in the development process the benefits that can be achieved when green and blue infrastructure (GBI) is delivered within an urban development setting and the important contribution it makes to delivering 'good growth' in Surrey. The document is in the form of a design guide and presents best practice examples of existing green and blue infrastructure projects that have already been delivered in the county and elsewhere, as well as signposting stakeholders to additional sources of information.

Ensuring that there is a suitable network of green and blue infrastructure in the county is a key concern for local authorities in Surrey and their strategic partners who are committed to delivering 'good growth' to benefit current and future residents. This approach, as echoed in our Surrey 2050 Place Ambition and the Community Vision for Surrey 2030, delivers upon the principles set out below and requires that good growth:

- Is sustainable, focusing on the places where people both live and work or locations where appropriate investment and interventions will enhance sustainability.

- Supports overall improvements to the health and well-being of our residents.

- Is supported by the necessary infrastructure investment - including green infrastructure (GI).

- Delivers high quality design in our buildings and public realm.

- Increases resilience and flexibility in the local economy.

- Builds resilience to the impacts of climate change and flooding.

- Is planned and delivered at a local level while recognising that this will inevitably extend at times across administrative boundaries.

The four areas of GBI that this design guide focuses on are set out in greater detail within the document, but these are:

- Urban greening

- Integrating green and blue infrastructure into new developments

- Green and active travel corridors

- Green links from urban to rural

This guide does not cover every aspect of green and blue infrastructure but aims to complement other strategies and guidance produced by the county council, borough and district councils as well as other strategic partners, such as the Surrey Nature Partnership. This document should be read in conjunction with the policies and guidance that each individual local planning authority has set out in their Local Plan and the design guidance for highways produced by the county council.

Our principles for green and blue infrastructure

Our approach to green and blue infrastructure (GBI) can be underpinned by the following principles:

Principle 1: First infrastructure

Green and blue infrastructure should be considered as Surrey's 'first' infrastructure and by ensuring that GBI is considered at the earliest stages of the planning process, our society, the environment, and our economy can benefit.

Principle 2: Optimise multi-functionality

Green and blue infrastructure is multi-functional. Therefore, the benefits to including nature-based solutions in our urban areas must be explored so that development is sustainable as well as fulfilling its primary purpose.

Principle 3: Connectivity is key

Green and blue infrastructure must be viewed as a strategic 'mosaic' of green and blue spaces that spans boundaries and opportunities must be taken to strengthen the connectivity of the GBI network. This will improve the links for core habitats as well as wildlife corridors themselves, allowing humans, animals and wider biodiversity to benefit.

Principle 4: Environmental net gain

Green and blue infrastructure is necessary not just to soften the impact that development has on our natural environment, but to ensure that it contributes a biodiversity net gain that results in an enhancement of the site compared to the pre-development baseline.

Principle 5: Context matters and local distinctiveness

Green and blue infrastructure must consider local context and character such as taking design cues from local habitat types, as described in Biodiversity Opportunity Area Policy Statements, while also serving local community needs.

Principle 6: Planned inclusively and collaboratively

Green and blue infrastructure management should create opportunities to engage communities and landowners in the planning, creation, enhancement, delivery and maintenance of nature-based solutions. Local involvement will embed green and blue infrastructure into the community and lead to better design and maintenance.

Principle 7: Public benefit for all

Green and blue infrastructure must deliver public benefits for all both directly and indirectly, including recreational and health and wellbeing benefits. Interventions to achieve public benefits should consider the needs of all social groups to ensure inclusivity.

Principle 8: Committing for the long-term

Green and blue infrastructure should be designed and delivered in a way that delivers benefits for future generations, including climate change adaptation and climate resilience. A key consideration will be maintenance of nature-based solutions, as set out in Principle 6.

Principle 9: An evidence-based approach

Green and blue infrastructure must be delivered using up-to-date evidence and analysis to deliver on the above principles such as connectivity, environmental net gain and public benefits for all. This approach should factor in monitoring and evaluation to ensure that progress can be evaluated.

Introducing green and blue infrastructure

What is green and blue infrastructure?

Green and blue infrastructure (GBI) can be described as all the individual parcels of natural space and features within both our urban and rural spaces that when connected, deliver quality of life and environmental benefits for communities and the nature that thrives within them as a result.

The individual parcels of green and blue infrastructure that link together to create a network includes conventional open spaces, such as parks, woodlands and playing fields, but also allotments, street trees, private gardens, green roofs and walls and sustainable drainage systems. Rivers, streams and other bodies of water are sometimes included within a definition of green infrastructure, although within this document we make the distinction between this blue and green infrastructure.

The benefits of green and blue infrastructure

Access to green and blue spaces is more important than ever, therefore it is vital that GBI is delivered across and within different spatial scales in order to contribute towards a patchwork of GBI that caters for different users. There are numerous advantages to better GBI for our communities, but developers will also see returns on their investment especially if the principles of planning inclusively and collaboratively as well as ensuring an evidence-based approach are followed. The list below (taken from Arup's Cities Alive booklet) shows a wide range of benefits that can be achieved with better green and blue infrastructure and helps us to understand how green and blue infrastructure serves numerous purposes, therefore becoming multifunctional in their use.

Environmental, economic and social benefits of green and blue infrastructure

Environmental benefits

- Improved visual amenity

- Enhanced urban microclimate

- Improved air quality

- Reduced flood risk

- Better water quality

- Improved biodiversity

- Reduced ambient noise

- Reducing atmospheric CO2

Economic benefits:

- Increased property prices

- Increased land values

- Faster property sales

- Encouraging inward investment

- Reduced energy costs via microclimate regulation

- Improved chances of gaining planning permission

- Improved tourist and recreation facilities

- Lower healthcare costs

Social benefits:

- Encouraging physical activity

- Improving childhood development

- Improved mental health

- Faster hospital recovery rates

- Improved workplace productivity

- Increasing social cohesion

- Reduction in crime

Of these benefits highlighted in the list above, research has been gathering pace in recent years on the improvements to physical, mental and social wellbeing that nature can provide to our communities. The Royal Horticultural Society (RHS) is one of these organisations leading the way in this field by investigating issues such as the decline of front gardens and the impact that this has on our wellbeing. The NHS Long Term Plan underlines the importance of social prescribing for healthy outcomes by training 1000 social prescribing link workers to work with patients to explore the outdoors and connect them with support services.

Planning for green and blue infrastructure at the earliest stage

Where new development is being delivered, sites must take a GI-led design approach to ensure that GBI is planned from the outset and contributes to the wider green and blue network. We want to see our parks, hedgerows and other natural assets not isolated but instead connected to other areas to improve the links for humans and wildlife.

This should be done by understanding how a place works including both what works well and what could be improved, as well as understanding site features such as topology, views, land uses and other environmental designations. Collaboration between partners (including between local authorities and developers), a willingness to invest, understanding and embracing new technologies and recognising the long-term benefits that GBI can offer to society are also required for multifunctional green and blue infrastructure to be delivered.

Green and blue infrastructure and climate change adaptation

The increased use of green and blue infrastructure can help to reduce some of the impacts of climate change we are likely to see this century, such as increased flood risk, heatwaves, droughts and changes to ambient temperatures. Green and blue infrastructure can deliver multifunctional benefits in urban areas including:

- decrease in risk of flooding through use of water storage and retention areas (e.g. ponds, canals, raingardens), and use of soil-covered surfaces over hard surfaces to facilitate drainage, which reduce surface runoff, discharge and slow tidal surges;

- temperature regulation provided by evapo-transpiration and shading from vegetation and airflow through open spaces;

- maintenance of freshwater quality and supply where sediments and pollutants are filtered through dense vegetation and soils (e.g. biofiltration swales);

- increase in thermal performance of buildings through use of green roofs and walls; and

- enhanced species resilience through provision of varied habitats and green corridors, which allow species to move easily to new climate spaces.

By integrating green and blue infrastructure into our new and existing developments we can make our spaces more resilient and, reduce costs and improve health and welfare.

Delivering green and blue infrastructure

The National Planning Policy Framework (NPPF) is clear that green and blue infrastructure is crucial in supporting sustainable development and that development must deliver an environmental net gain on site. The Government's 25 Year Environment Plan also sets out details for how a Nature Recovery Network will use Local Nature Recovery Strategies to restore protected sites and bigger, better and more connected wildlife-rich habitats.

National Design Guide

The National Design Guide, released in early 2021, provides practical design guidance to those involved in the design process. Green and blue infrastructure features prominently by detailing how smart, nature-based solutions can contribute to a network of multifunctional GBI space. Some of the solution that could be adopted include:

- Communal roof terrace

- Open space well overlooked by homes

- Outdoor gym equipment

- Trees provide shading for seated areas

- Natural play alongside sustainable drainage systems basin

- Formal hedging marks out the play and picnic table area

- Seating for people to rest

- Cycle parking

- Rain gardens

- Community managed raised beds for food growing

- Small trees in gardens provide shading, screening and additional privacy

- Informal doorstep play

- Trees provide different street character to main square

- Rain gardens within the street

- Soft landscape in front gardens and along front boundaries

The guide prompts questions to not only make sure that nature is present within our urban areas, but that it also contributes towards biodiversity net gain, addresses the impact of climate change and leads to well-designed places that are visually attractive and locally distinctive.

Natural England Green Infrastructure Framework

In January 2023, Natural England launched their new Green Infrastructure Framework which supports the greening of our towns and cities and connections with the surrounding landscape. The framework aids not only local planning authorities and developers to meet requirements for the planning and delivery of green and blue infrastructure as per the National Planning Policy Framework (2021), but it also supports smaller organisations and groups to consider green and blue infrastructure in their local areas.

The framework is also accompanied by a set of standards that define what 'good' GI looks like as well as an interactive mapping service which provides a baseline of green and blue infrastructure across England with multiple data sets that assist in planning GBI strategically at different scales and targeting investment where it is most needed.

Additionally, the framework includes other resources including the Environmental Benefits for Nature Tool (ENBT) which highlights impacts of proposed land use change on the services nature provides across 18 ecosystems over a 30 year period. As well as demonstrating GI Processes and journeys for developers, neighbourhood planning groups and local authorities.

Local plan policies

Local plans include policies and guidance on green and blue infrastructure, in addition to policies on wider issues related to green and blue infrastructure (such as townscapes, landscape character, nature conservation) in order to facilitate safe, healthy and prosperous neighbourhoods. Table 1 shows which local plan policy relates to green and blue infrastructure from each local planning authority in Surrey.

Table 1: Surrey local authorities local plan green and blue infrastructure policy

| Local authority and local plan | Overarching green and blue infrastructure policy |

|---|---|

| Elmbridge Core Strategy (2011) | Core Strategy (CS) Policy 14 – Green Infrastructure |

| Epsom and Ewell Core Strategy (2007) | CS4 – Open Spaces and Green Infrastructure |

| Guildford Local Plan: strategy and sites 2015 to 2034 (2019) | ID4 – Green and Blue Infrastructure |

| Mole Valley Local Plan (2020 to 2039) | CS 15 – Biodiversity and Geological Conservation, CS 16 Open Space, Sports and Recreation Facilities, EN9 Natural Assets, EN10 Open Space and Play Space |

| Reigate and Banstead Core Strategy (2014, renewed in 2019) | CS2 Valued landscapes and the natural environment |

| Reigate and Banstead Local Plan Development Management Plan (2019) | NHE4: Green and blue infrastructure |

| Runnymede 2030 Local Plan (2020) | EE11: Green Infrastructure, EE12: Blue Infrastructure |

| Spelthorne Core Strategy and Policies Development Plan Document (2009) | SP6: Maintaining and Improving the Environment, EN1: Design of New Development |

| Surrey Heath Core Strategy and Development Management Policies 2011 to 2028 (2012) | CP13 Green Infrastructure, DM10 Development and Flood Risk |

| Tandridge Core Strategy (2008) | CSP15 Environmental Quality, CSP18 Character and Design |

| Waverley Local Plan Part 1: Strategic Policies and Sites (2018) | NE2 Green and Blue Infrastructure, CC1 Climate Change |

| Woking Core Strategy (2012) | CS7 Biodiversity and nature conservation, CS17 Open space, green infrastructure, sport and recreation |

| Woking Development Management Policies Development Plan Document (2016) | DM1 Green Infrastructure Opportunities |

Supplementary Planning Documents (SPD) are non-statutory documents that provide further guidance to support policies set out in borough and district local plans. These documents can provide more specific information relative to the local planning authority area that will be of use to developers and others.

Notable examples of SPD's that cover green and blue infrastructure are Runnymede Borough Council's Green and Blue Infrastructure SPD and the Reigate and Banstead Borough Council's Climate Change and Sustainable Construction SPD.

The Colne Valley Regional Park have produced a Green Infrastructure Strategy. The Colne Valley Regional Park covers 10 Local Planning Authorities including Spelthorne Borough Council. The strategy aims to bring Green and Blue on the map to the forefront in planning decisions and feature the landscape of the Valley as a whole rather than the council boundaries.

Strategies in Surrey that contribute towards green and blue infrastructure

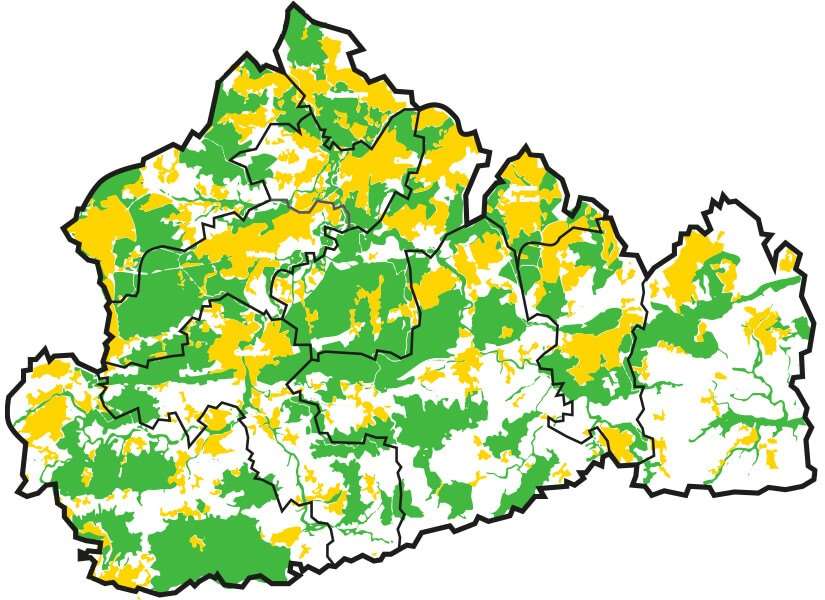

Surrey's Local Nature Recovery Strategy

The Local Nature Recovery Strategy (LNRS) for Surrey will establish priorities for nature recovery and will map proposals for specific desirable land use and land management actions to deliver these priorities, across the county.

Surrey County Council is responsible for producing the LNRS for Surrey and, in subsequent years reporting on progress and updating it.

Each LNRS will join up with neighbouring areas and as such, will form a key strand of the Nature Recovery Network across England. Simultaneously each LNRS will be detailed enough to help inform proposals and decisions of individual landowners and farmers, developers, and regulators including local planning authorities.

Surrey's LNRS will be developed in a transparent and collaborative manner, in line with national regulations and guidance. It will build collaborative, landscape-scale actions within and beyond Surrey.

Surrey's Health and Wellbeing Strategy

The Surrey Health and Wellbeing Strategy is a partnership document between the county council, the NHS, district and borough council partners as well as wider partners.

Although Surrey performs well on several key health and wellbeing metrics, there are still some causes for concern especially where pockets of deprivation exist. One in four children leave primary school in Surrey as overweight or obese whilst more than 1 in 5 adults in Surrey are classed as inactive, undertaking less than 30 minutes of activity per week. There is also a divide between socioeconomic groups, with 28% of those from lower income groups inactive compared to 13% from higher income groups. The priority of the strategy therefore focuses on helping people to lead healthy lives, not just by focusing on the decisions that individuals make but also by considering how the built environment can impact health outcomes.

Active Surrey's Movement for Change document is a physical activity strategy that supports Surrey's Health and Wellbeing strategy and acts as the blueprint for a new way of working for individuals to adopt a more active lifestyle. One of the aims of this document is to create a long-term vision for a greener county with active lifestyles at the heart of future transport and infrastructure planning, therefore highlighting the links that can and must be made between the built environment and healthy outcomes.

Healthy Streets for Surrey Design Guidance

Surrey County Council, in collaboration with Create Streets, has produced new Healthy Streets for Surrey Design Guidance which draws best practice principles from a range of guidance and highlights what Surrey's streets in the future should look like.

The guidance discusses ways to achieve sustainable streets, such as developing safer walking and cycling routes, promoting public transport, and engaging with local communities. To support the practical implantation, the website has resources and guidance for developers, residents and councils to design and implement Healthy Streets strategies.

Overall, the guidance encourages a shift towards more people-centric and environmentally friendly street design to create vibrant and healthier communities.

Sustainable Drainage Systems (SuDS) Design Guidance

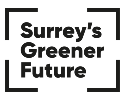

As the Lead Local Flood Authority for Surrey, the county council is the risk management authority responsible for determining local flood risk and assessing surface water flood-risk in relation to major development proposals in the county. The Sustainable Drainage System Design Guidance sets out what Surrey County Council expects to see when a planning application is submitted. Diagram 1 sets out that SuDS design should consider four important aspects:

- Water quantity - control the quantity of runoff to support the management of flood risk, and maintain and protect the natural water cycle;

- Water quality - manage the quality of the runoff to prevent pollution;

- Biodiversity - create and sustain better places for nature; and

- Amenity – Create and sustain better places for people.

Diagram 1: Key themes for the design of SuDS

Water courses are under significant pressure especially in our urban areas so effective SuDS design can deliver multifunctionality into schemes as well as biodiversity net gain through greater retention of water and better water quality. Examples include the use of swales, ponds and attenuation or infiltration basins.

Urban focus of this guide

This next section introduces the four key themes for this guide: urban greening, integrating green and blue infrastructure into new developments, green and blue corridors, and green links from urban to rural. These four themes are designed to raise the standards of development in Surrey whilst also optimising our natural capital assets. The themes below provide evidence for the recommendations made whilst best practice from case studies in Surrey and further afield are introduced, with greater detail set out in the annex.

Urban greening

Urban greening focuses on the small-scale interventions needed to transform both public and private pressurised urban spaces to improve the place offer of our towns. By implementing greener interventions such as wild planting and rain gardens, some of the most undesirable impacts of urban development such as declining rates of biodiversity and an increased chance of surface water flooding can be reduced thereby also decreasing the pressure on urban land use.

Urban greening contributes towards a larger interlinked network of green space and assets for biodiversity and wildlife to thrive, therefore filling in 'gaps' in areas that have traditionally lacked such natural assets.

Urban greening in more detail

This section covers interventions that can be delivered in an established urban environment or for sites that amount to minor development. There is typically more emphasis on green and blue infrastructure being provided in major developments of 10 residential units or more, compared with smaller sites, but all development of any size and type can contribute towards the green and blue infrastructure network. In order to measure biodiversity net gain, Natural England have produced a small sites metric that can typically be used on sites between one and nine residential dwellings or where the site is less than 0.5 hectares.

Individual householders will need to consider and undertake green and blue measures if we are to achieve a landscape-scale green and blue infrastructure matrix within our built-up areas. This will include retaining and improving natural assets in situ such as hedgerows or small water bodies, as well as considering how a single dwelling can contribute towards the local green and blue infrastructure network, such as extending a hedgerow or allowing a wildflower 'meadow' to grow.

There is an increasing offering of guidance and best practice that can guide development, such as the Urban Green Factor tool adopted within the London Plan. It should be noted that no Surrey authority has currently adopted an Urban Greening Factor and that this is included for guidance purposes only. Whilst the measures below will all provide their own tangible differences, each location must be assessed on its own merits to understand the special characteristics of that area and how green and blue infrastructure can contribute most to the local network.

Trees

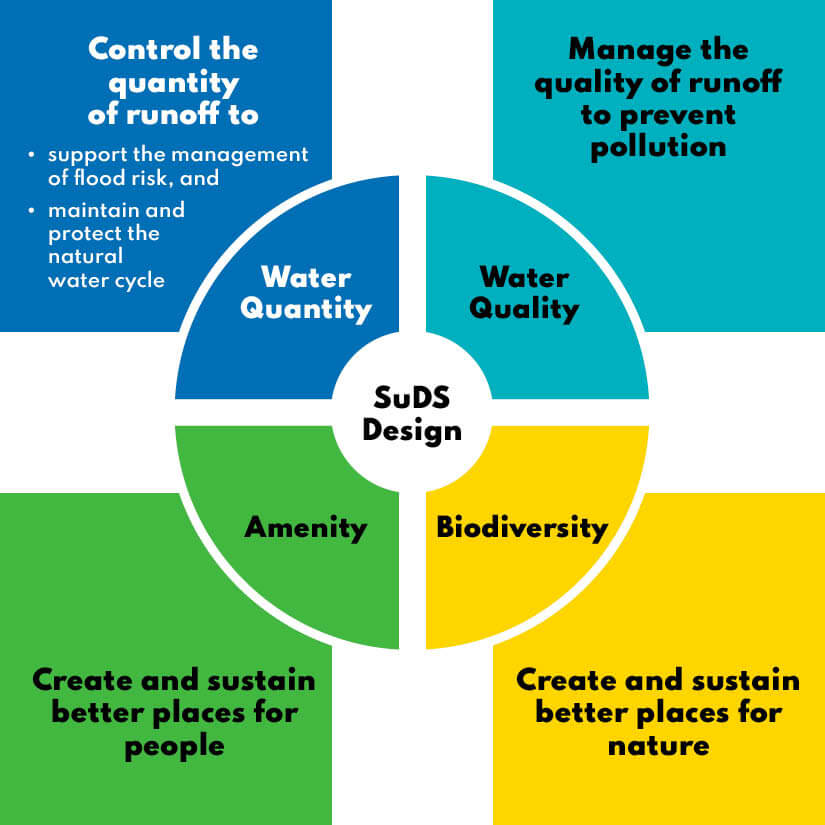

Planting more trees in urban areas is usually the first measure when considering urban greening and certainly trees do help with issues such as the 'heat island effect', encouraging more biodiversity into our urban areas and providing a natural drainage feature. In order to realise the benefits of tree planting in urban areas, there are a number of factors spanning the site constraints, tree ecophysiology, ecosystem services and aesthetics that should be considered to determine the correct tree to be planted (see also diagram 2 below. The factors from diagram 2 are listed in appendix 3: considerations for tree selection within urban environments).

Tree planting serves as a natural barrier that can replace more traditional 'grey' hardstanding and more manufactured solutions, or even to provide a soft screening between two separate land uses. Surrey's New Tree Strategy is supportive of tree planting on the highway provided that the right tree or shrub is planted in the right location and is supported by adequate maintenance, such as the staking of any new tree as it grows. Chapter 7 of our forthcoming Healthy Streets for Surrey Design Guide provides more information on the importance of street trees and on tree planting considerations. The requirements for space for a new tree to grow on the highway and considerations such as tree pits to be utilised on footways make new developments where sustainable drainage systems are present make designing trees into the built environment more achievable. Appendix 4 of Surrey's New Tree Strategy provides further detail on the required design guidelines for highway tree planting and verge management.

Tree planting serves as a natural barrier that can replace more traditional 'grey' hardstanding and more manufactured solutions, or even to provide a soft screening between two separate land uses. Surrey's New Tree Strategy is supportive of tree planting on the highway provided that the right tree or shrub is planted in the right location and is supported by adequate maintenance, such as the staking of any new tree as it grows. Chapter 7 of our forthcoming Healthy Streets for Surrey Design Guide provides more information on the importance of street trees and on tree planting considerations. The requirements for space for a new tree to grow on the highway and considerations such as tree pits to be utilised on footways make new developments where sustainable drainage systems are present make designing trees into the built environment more achievable. Appendix 4 of Surrey's New Tree Strategy provides further detail on the required design guidelines for highway tree planting and verge management.

Street trees also contribute to better air quality by filtering out harmful levels of pollutants from vehicles and industry and do so better when they are near the source of air pollution. Although trees can improve air quality locally up to 300 meters, their impact is felt most at up to 30 meters from the roadside with a total of 5.5kg of carbon sequestered per tree annually (see page 12 of the UK Green Building Council report for a summary of the benefits of urban nature based solutions). As a result, tree-lined streets and boulevards provide benefits for uses such as retail and hospitality by delivering a better visitor experience that encourages greater spending and more time spent in those districts.

With more trees present, shade is provided to building users providing an average temperature reduction in urban areas of 3°C which reduces the need for air conditioning and improves the wellbeing of building occupants. These lower temperatures that trees provide also decreases the risk of harmful pollutants like ground level ozone that commonly spike on hot days in urban areas. Like green walls, there are certain species (see table 3 below) of tree that are known for their hardiness and low maintenance requirements, as well as having bigger canopies and hairy, waxy leaf structures that better suited to filtering out harmful pollutants.

Street trees enhance traffic calming measures by reducing the average speed of drivers and reducing crash rates and are preferred to speed humps; taller trees especially give the perception of a narrower street whilst closer spaced trees give an illusion of speed. Measures such as these reinforce pedestrians as the top priority in the hierarchy of street users and help to increase the number of active travel journeys, one of the goals of the Surrey Health and Wellbeing Strategy and Surrey's Local Transport Plan 4.

Type of tree suitable based on available space and specific features

(Adapted from Surrey's New Tree Strategy and Tree Species Selection for Green Infrastructure: A Guide for Specifiers)

Small trees (5 to 12 meters) requiring 10 meters3 and a minimum width of 1.1 meter to grow:

- Prunus Royal Burgundy (Royal Burgundy) - This tree has reddish-black leaves that lighten in Autumn and produces pink flowers appearing in Spring.

- Ligustrum Lucidum 'Excelsum Superbum' (Chinese Privet) - This tree is an evergreen with glossy light leaves. Flowers creamy white in late summer followed by black berries. This tree acts as good hedging and screens.

- Corylus Colurna 'Te Terra Red' (Hazel) - This tree produces leaves that are red in Spring and then turn purple or green until leaf fall.

- Gleditsia Triacanthos f. inermis 'Sunburst' (Honey Locus) - A small deciduous tree with a rounded crown. This tree produces golden yellow leaves in summer that turn green later.

- Koelreuteria Paniculata (Pride of India) - A generally disease-free deciduous tree that have a shade of pink and later yellow leaves, followed by fruits.

Medium height (12 to 17 meters) Requires 20 meters3 and a minimum width of 2 meters to grow:

- Acer Campestre (Field Maple) - A bushy, deciduous tree with leave that turns yellow-red in autumn. Small flowers transition to maple fruits.

- Pyrus Calleryana 'Chanticleer' (Callery Pear 'Chanticleer') - A conical-shaped tree with dark green leaves and white flowers followed by small fruits. This tree can be exposed or sheltered from the elements.

Large height (over 17 meters) Requires 30 meters3 and a minimum width of 3 meters to grow:

- Fagus Sylvatica (Common Beech) - A deciduous tree with a broad crown native to the UK. Yellow green in Spring followed by brown in Autumn. Harvests bristly fruits

- Acer Pseudoplatanus (Sycamore) - A deciduous tree with dark green leaves, with yellow-green leaves leading to green fruits. This tree can tolerate almost any conditions.

- Ginkgo biloba (Maidenhair tree) - A deciduous tree that starts off conical but becomes irregular with age. Its leaves turn clear yellow in autumn with fruits. This species is pollution tolerant.

The Healthy Streets for Surrey Design Guidance provides more details on Street Trees. Section 7 covers planting principles for street trees and greenery for new developments and retrofit schemes. It outlines that there is opportunity to create tree-lined routes and achieve ecological goals to regreen existing urban streets. It also complements guidance set out in the National Planning Policy Framework (2021) and planning practice guidance as well as district and borough local plans and supplementary planning documents (SPD's).

Diagram 2: Considerations for tree selection within urban environments

The planting of trees however should be based on evidence such as 'Tree Species Selection for Green Infrastructure: A Guide for Specifiers' that will ensure that the right tree is planted in the right place. The Trees and Design Action Group's guide goes into significant detail around the right conditions for each tree, such as space available, soil conditions and aesthetic preferences etc, as seen in the diagram above.

In urban areas, tree planting pit design for street trees will particularly need to be considered, so that when planting into hard surfaces, cellular (crate) systems should be considered that provide optimum soil conditions for root growth, such as these Pavement Support Systems. Trees that are intended to be planted on paved, impermeable hardstanding will need to be resistant to drought whilst access to the quality and quantity of light must also be a consideration.

When planning for trees in urban areas, importance should also be attached to 'designing in' large-canopy, long-lived trees as these provide the greatest green infrastructure benefits. Once again, this means considering green and blue infrastructure and landscape design at the outset of a project to ensure sufficient space is dedicated to such trees. Methods are increasingly being used to estimate the monetary and other values (e.g. canopy cover) of trees as part of green infrastructure and natural capital, for example, i-Tree Eco, with organisations such as Treeconomics being able to provide this analysis.

Case study: Cobham Services (M25 J9/10)

The Cobham motorway service station on the M25 is just one example of how green infrastructure can be brought to areas of hardstanding such as car parks, which are not typically considered multifunctional areas.

Green infrastructure is placed around the site to soften the necessary grey infrastructure installation and support nearby retained greenbelt land. Trees are placed within tree pits that use a modular system to help to support the tree in its position whilst also allowing for storm water harvesting that supports the wider SuDS on-site.

Other methods to improve the greening of urban areas

The use of plants is clearly an effective way of achieving some of the benefits set out earlier. Green and interesting environments can help to create a diverse and interactive environment that individuals want to spend time in, such as the river location in the image below, whilst installing a sense of civic pride. The visual impact of planting itself can encourage people to spend more time outside for their health and wellbeing as well as taking 'greener' routes for transport purposes as set out in the Green and active travel corridors chapter.

Urban greening can also help to mitigate the decline of our high streets. From spending more time in local pocket parks or on more naturally diverse streets to outdoor dining, greater urban greening increases footfall to those areas and premises that are near nature including a 30-50% increased restaurant patronage.

Living walls

As shown in the case study below, living walls are a good example of what can be done to address air quality in urban areas. Thousands of plants from different, but ideally native species can be specifically selected for the function of improving air quality. Those plants which are hairy, sticky or waxy are far better at trapping particulates such as PM10, PM2.5 and even PM1 that are generated through activities such as construction and transport, removing up to 35% of NO2 in the 'street canyon'.

Table 2: Type of living wall suitable based on available space and specific features

| Type of wall | Details |

|---|---|

| Green façades | Perhaps the most common green wall, these walls feature plants that are rooted in the ground or into planter boxes and can be directly grown onto the wall or trained against wires or trellises. Although they may take time to establish, little maintenance is required and rooted plants many not require irrigation. |

| Living walls | Living walls use textiles, plastics and metal (boxes and cages) to provide pockets or troughs that hold either substrates or another material such as foam to support plants. Such walls are usually irrigated, sometimes via pumps that use sensors to detect moisture levels below a certain threshold, but other walls may use a different system, such as collecting rainwater runoff from roofs. |

| Bioactive façades | Research is ongoing into producing building materials that will be able to accommodate opportunities for self-supporting vegetation like algae and mosses. This option will create an inexpensive, low maintenance green wall where green façades or living walls may not be possible. |

Table adapted from "Living Roofs and Walls, from policy to practice - Designing Buildings", Greater London Authority, 2019.

Plants suitable for this type of use are a mixture of evergreen and perennial plants that are known to thrive in a busy, urban environment and provide a continuous living surface in all seasons. Typical energy savings compared to an adjacent space are roughly 8% whilst the reduction in indoor temperature from a green facade is 2.7°C.

For living walls such as Duke's Court and others in Woking, plants can be grown in natural soil within 'modules' that can then be transported to the site to be planted in the wall. The average installation cost (£ per meters2yr) for a green façade is £282 compared to £702 for a living wall, whilst the average maintenance cost (£ per meters2yr) for a living wall is £38.

Case study: Dukes Court Plaza, Woking

A 'living wall' has been installed on the central core of the Duke's Court office block and it is believed to be the largest living wall in the UK outside of London.

A 'living wall' has been installed on the central core of the Duke's Court office block and it is believed to be the largest living wall in the UK outside of London.

Standing at 40 meters tall and covering an area of 460 meters2, the living wall provides sources of nectar, an alternative ecological habitat through the use of soil and bird boxes, with a changing aesthetic through the seasons providing a variety of pollinators.

The species of plant selected for the wall are well known for their air purification properties which will improve the air quality of the plaza area. There are also bird boxes and insect hotels that have been placed into the modules that make up the structure of the wall.

Attracting biodiversity to roof spaces

Retrofitting our urban spaces to become greener should involve the auditing of all surfaces to understand those that are not being used to their full potential. For most towns and cities in the UK, it is the roofscape that offers an exciting potential to contribute to a stronger GBI network. On Surrey's doorstep, London has some notable examples of skyline and rooftop spaces being used recreationally in addition to undisturbed biodiversity recovery spaces.

Photo © Bauder

The type of roof covering used will very much depend on the future use that the roof will have, and three different uses can be found in the table below. A good option are sedum roofs, such as in the photo above (from Bagshot), that offer an instant growing roof that is light weight, green all year round and requires little maintenance. Although a sedum roof option delivers the flexibility required in urban environments, wildflower roofs and biodiverse roofs (that mimic the existing surrounding environment) could also be explored, with all three options offering improved visual amenity and better wellbeing conditions for residents in the vicinity.

The photo below shows the bus stops which will be installed around Surrey. The living roof will help support native biodiversity, help create healthier local communities, and bring greenery back into urban areas.

The economic advantages to greening roofs are also beneficial for developers and building owners as well as occupants of the building. Energy savings for building occupants are roughly 6.7%, uplift to property value can be 6.9% whilst an 11db noise reduction is delivered with a green roof. Installation costs (£ per meter2) are on average £126 for an extensive roof and £176 for an intensive roof whilst maintenance costs (£ per meter2) are £6 and £11 respectively.

All three of the options below will also reduce the rate of surface water runoff, which will help to negate the instant impacts of severe weather events, however the London Plan's Urban Greening Factor rates intensive roofs as most desirable.

Table 3: Type of roofs commonly used and their common features

| Type of roof | Details |

|---|---|

| Extensive roofs | These roofs are lightweight and require little maintenance or watering, therefore, are ideal for homeowners. Depth of vegetation is usually 80-100 millimetre high using plants such as grass, moss, sedum or small flowers with sedum being the most popular choice due to its hardiness and requirement for low maintenance. Mat-forming species of Sedum, Sempervivum and moss are traditionally used but for dry, shady areas, ferns should be considered. |

| Intensive roofs | This option is more appropriate when catering for recreational use and including a larger variety of planting such as bushes and small trees. Designed for sturdier buildings and larger projects, a much deeper substrate will be required in addition to irrigation requirements. As a result, maintenance and management of these roofs will need to be factored into the design. Drought tolerant plants should be used for this type of roof. |

| Semi-extensive roofs | Although sitting somewhere between the two options already laid out, semi-extensive roofs closer resemble extensive roofs as they are still not suitable for trees and bushes. They can however cater for a larger variety of planting compared to other extensive roofs with 100-200 millimeter of substrate typically used. Dry habitat perennials and ornamental grasses are suitable plants to use. |

Information sourced from Green Roofs and Green Roof Systems – Create A Sedum Roof

Case Study: Quadrant House, Caterham

The image shows the intended improvements that are planned at Quadrant House as part of the wider Caterham and North Tandridge Regeneration Programme.

Improvements to the development enhance the roadside façade by introducing a living wall and a roof terrace at third floor level.

Illustration © Jon Sheaff and Associates

Planting as a natural barrier

Planting that serves as a natural barrier is another method of urban greening that can replace 'grey' hardstanding and more manufactured solutions. It can also encourage positive behaviour change and improve security while at the same time delivering multifunctional benefits. The Surrey Street Design Guidance highlights the impact that planting can have in delivering healthy urban environments and reversing the decline of high streets so that communities feel that they can spend time in these areas and feel safe.

Measures such as the raised planter boxes help to reinforce pedestrians as the top priority in the hierarchy of street users and due to reduced vehicular traffic, encourage an increased number of active travel journeys which is one of the goals of the Surrey Health and Wellbeing Strategy. Further planting of natural barriers on the roadside will reduce the level of harmful pollutants arising from vehicle movements, with natural barriers comprised of solely hedgerows being able to remove up to 63% of pollution exposure and proving to be the most effective.

Green features that are existing assets on site such as trees and hedgerows should always be retained where possible but if this is not possible or additional screening and barriers are required, native plant species should be used to not disturb the local ecological environment. Walls and fences installed in and around a property should assist in providing a habitat to local species with planting facilitated in or next to those features. Wildlife-friendly boundaries and barriers help to connect small mammals with gardens in the wider neighbourhood and therefore to the wider green and blue infrastructure network, with hedgehogs benefiting specifically.

The economic impact of more naturally diverse streets is overwhelmingly positive for not just property prices and for the residents that live in the area, but also for businesses in our towns and villages. For example, restaurants that are near trees and other urban greenery experience an increase in patronage of between 30 and 50%. These venues may also experience an increase in customers willing to sit outside and enjoy these natural assets when the weather is pleasant, therefore adding further economic value.

Other opportunities for urban green planting

Allotments are valuable assets that should be safeguarded, but there are alternative green spaces that can offer greater social interaction and involvement with our natural surroundings. The National Planning Policy Framework (2021), alongside requiring every new street to be tree-lined, also recognises the value of ensuring that trees are delivered elsewhere on a site such as through the implementation of community orchards. This measure, alongside others such as herb gardens, would help to foster social interaction between individuals of all ages and backgrounds and provide a public benefit for all.

Solutions to capture and reduce impact of rainwater

The effect of climate change is likely to lead to an increased amount of precipitation and flash flooding, which will cause strain on Surrey's urban areas and rivers leading to fluvial as well as pluvial flooding. Surrey is under intense pressure to deliver residential development alongside the cumulative impact from residential extensions yet has several rivers and waterbodies running through including the Wey, Mole and Thames. It is therefore vital that natural solutions are used to create a more 'water-friendly' urban environment in part by encouraging developers to work with councils and other bodies to maintain water bodies for all.

Rain gardens, such as the scheme installed in Woking by Surrey County Council shown in the photo, is one measure that can be created within the urban environment to capture, store and slowly release rainwater runoff back into the surface water network whilst increasing biodiversity in these locations. They are a low maintenance measure that utilise perennials plants that do not require watering, and rain gardens can also reduce the need to create a soakaway or connect to other sewers. As a demonstration for the need to consider context when planning in green and blue infrastructure, rain gardens can typically absorb up to 30% more rainfall than a lawn, making the decision as to which green or blue measure installed important.

Surrey County Council are continually investigating and programming schemes to mitigate the impact of surface water in high flood risk areas. In addition to a planned flood storage scheme on Horsell Common SANG that will help reduce downstream flood risk to housing within Woking, rain gardens are being designed to store storm water within the more urban areas of Woking town with several already installed. Other complimentary initiatives are also being undertaken, including advising residents on other drainage solutions and working with adjacent landowners to ensure that ditches are kept free flowing.

Case study: Merstham Primary School, Redhill

In August 2020, Merstham Primary School suffered from serious flash flooding that left 80% of the school unusable with extensive refurbishment works required to reopen the rest of the school.

To minimise the chances of similar flooding impacts occurring again, one of the changes made was to locate SuDSPlanter units around the school site, as shown in the image below, to manage rainwater run off by capturing and attenuating the flow into the drainage system. This measure also has the added benefits of providing an educational experience for the pupils at the school by allowing them to get involved with the installation of planters right through to the ongoing planting, as well as increasing biodiversity on-site.

Photo © SuDSPlanter

Integrating green and blue infrastructure into new developments

When a site is allocated for development, it provides an opportunity for a development to safeguard the flora and fauna in and around the site that is beneficial to local ecology whilst also delivering green and blue infrastructure that ensures a biodiversity net gain. Every effort should be made to ensure that biodiversity net gain is delivered on-site in order to mitigate the impact of development in that location.

Every opportunity should be made to engage with the local community to design a space which will serve their needs. More on this can be found in the stewardship and community involvement section.

Master planning for new developments

For large sites that have been allocated in the Local Plan, green and blue infrastructure should be designed in from the outset to ensure that it comes forward as part of the final masterplan. Surrey County Council encourage developers to engage with the pre-application services offered both by internal services such as the flooding team to consider surface water risk, as well pre-application services offered by the local planning districts and boroughs themselves. Once a site reaches the application stage, it is often too late for Development Management planning officers to significantly alter the scheme or for other aspects to be designed in. Development that takes account of local assets will create a vibrant, attractive and healthy ecosystem for both residents and wildlife which in turn, creates a desirable settlement for developers to release to the market.

Smaller sites can also contribute towards the strengthening of green and blue networks and corridors across the county. Many of the measures set out in the section on 'urban greening' are simple measures that can be included anywhere, whilst smaller schemes may also be able to contribute to go further by linking with green and active travel corridors or improving the links from urban to rural areas depending on where those sites are situated.

If a site can increase the likelihood of residents spending more time locally within and in the immediate surroundings of a development, a lower carbon footprint can be attached to that development due to reduced vehicular emissions, the local economy will be better supported which results in a stronger sense of place, as demonstrated with the Kidbrooke Village example below. The following is by no means an exhaustive but by undertaking some of the steps outlined below, developments can maximise their green and blue infrastructure potential.

Case study: Kidbrooke Village, southeast London

Although not in Surrey, Kidbrooke Village (page 34 of the Demystifying Green Infrastructure report), in southeast London, is a good example of a scheme that has undergone a successful master planning redesign which involved extensive community involvement.

Photo © Berkeley Group

The site was formerly one of the most deprived areas in the country in part due to inward-facing design and a lack of green space. However, the new development masterplan focused on permeability and connections to green spaces with 50 acres of new parkland and open space created and 2000 new trees planted, earning the scheme the Sir David Attenborough Award for Enhancing Biodiversity. Ecological as well as health and wellbeing benefits have been delivered side-by-side.

Facilitating green and blue infrastructure in new developments

Increasing green and blue infrastructure in new and existing communities is clearly the UK Government's 25-year plan for the environment, so it makes good sense to plan for biodiversity net gain (BNG) on site. In addition to the measures introduced in other chapters of this guide, many of the initiatives adopted under various mechanisms such as the Urban Greening Factor in London could be introduced into a development of any size however, some of the more impactful measures will only be viable on a larger site and therefore require planning in from the start.

For larger new developments, a clearly identified parcel of land should be set aside for green space use which should be secured via the most appropriate planning mechanism available. Waverley Local Plan Part 1: Strategic Policies and Sites (2018) (Policy SS5 - page 175 of Waverley Local Plan part 1) 'Strategic Housing Site at Land South of Elmbridge Road and the High Street, Cranleigh' states that in support of 765 new homes, a linear park will be delivered along a public right of way including a landscaped buffer of trees and hedgerows, a buffer zone will be created and maintained along existing streams and that reservoirs included within the site boundary will be enhanced in recognition of their amenity and ecological value. The size of the development area will often determine the extent of green and blue infrastructure that can be incorporated with it important that sites deliver the maximum potential for green and blue infrastructure benefits. For large sites where a site has multiple delivery phases, green spaces should be delivered earlier to ensure that the first occupants of a development can benefit.

To ensure they serve multifunctional purposes green spaces should consist of more than just areas of cut grass, link to a wider green and blue infrastructure network and offer flexibility so that they cater to a range of ages and uses, for example through wildflower meadows, community gardens and space for games. Pathways and corridors should be easy to follow yet stimulating, and follow guidance set out in the active travel networks sections as well as in our forthcoming Health Streets for Surrey Design Guide. This may include creating developments that do not promote the private car by for example, limiting car parking spaces and designing residential streets that naturally slows down traffic through corners, planting and street widths. Finally, communal and public areas should feel safe with areas that provide natural surveillance and are naturally lit during the day with artificial lighting to be used for security at night.

In addition to delivering homes that are built to sustainable technical standards, current good practice is for new developments to achieve biodiversity net gain by following the 'mitigation hierarchy' on site:

- do everything possible first to avoid impacts

- minimise predicted impacts on biodiversity and ecosystem services

- assess the current quantity and condition of natural assets with the development footprint and what (ecosystem) services they are providing to society

- determine whether creation of additional assets or restoration or improvement of natural assets could enhance the benefits provided as part of the development and the wider area

- as a last resort, compensate for losses that cannot be avoided, preferably within the development footprint

- if this does not generate the most benefits, then these can be provided elsewhere.

Case study: Priest Hill Nature Reserve

The project located in Ewell (page 24 of the good practice guidance on Biodiversity Net Gain), turned former playing fields and some previously developed land that was suffering from neglect into a 34-hectare nature reserve through planning gain as a result of a 1.7 hectare, 15 homes development. Combined Counties Properties and Cala Homes worked closely with the Surrey Wildlife Trust (as well as Epsom and Ewell Borough Council) to ensure that the best possible results were realised on-site, as well as transfer ownership to the Trust.

Photo © Mike Waite

Positive results from the project include improved lowland calcareous grassland cover, an increase in hedgerows and the presence of previously lost butterflies to the area. A rare small blue butterfly has now been recorded on site. The 'green' network in the area has become better linked with the Howell Hill Nature Reserve and Epsom Downs lying to the south in an important strategic green infrastructure corridor.

Mitigating flood risk

One of the key aspects of green and blue infrastructure in new developments is flooding, whether this be dealing with an existing issue on site or mitigating against the impacts that can arise from new development and increased hardstanding. The National Planning Policy Framework (2021) aims to direct developments away from areas that are classified as at high flood risk but if development must take place in the floodplain, it should be mitigated without increasing flood risk elsewhere. As a minimum, Sustainable Drainage Systems (SuDS) must be incorporated within all new development in order to minimise as far as possible the risk of surface water flooding on the development site and to the surrounding area.

The Department for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs (DEFRA) has developed its own Non-Statutory Technical Standards (NSTS) that guides developers on the design of the proposed drainage system. As the Lead Local Flood Authority (LLFA) for Surrey, the county council has also produced the Sustainable Drainage System Design Guidance (SuDS planning advice) setting out what it expects to see forthcoming from development to manage the flood risk from surface water, groundwater and ordinary watercourses. SuDS are considered within the Healthy Streets for Surrey Design Guide. Section 8 provides details on sustainable water management including location of SuDS features, choice of SuDS for streets and SuDS maintenance.

In addition to safeguarding occupants and neighbours of the development site from flooding, the design of the drainage system should, from the outset, consider opportunities for inclusion of amenity and biodiversity objectives and thus provide multi-functional use of open space. Examples of such SuDS interventions are wetland, underground storage, green roofs, rainwater harvesting, soakaways, filter strips, permeable paving, bioretention area, swale, hardscape storage and pond/basin. These interventions reflect principle 2: optimising multi-functionality as well as principle 4: increasing environmental net gain. Above-ground, nature drainage interventions can perform the same function as grey, below-ground infrastructure whilst delivering additional ecosystem services.

In addition to safeguarding occupants and neighbours of the development site from flooding, the design of the drainage system should, from the outset, consider opportunities for inclusion of amenity and biodiversity objectives and thus provide multi-functional use of open space. Examples of such SuDS interventions are wetland, underground storage, green roofs, rainwater harvesting, soakaways, filter strips, permeable paving, bioretention area, swale, hardscape storage and pond/basin. These interventions reflect principle 2: optimising multi-functionality as well as principle 4: increasing environmental net gain. Above-ground, nature drainage interventions can perform the same function as grey, below-ground infrastructure whilst delivering additional ecosystem services.

For larger sites, site design as well as the materials used should be considered in order to reduce flood risk whilst runoff should be managed as close to the source as possible. SuDS efficiently manages any excess rainwater, such as the swale featured in the River Walk development, and by using several SuDS options in tandem, runoff can be filtered as well as slowed down before it escapes.

Photo © SuDSPlanter

Case study: River Walk (River Lane Yard), Fetcham, Mole Valley

The River Walk development of 26 residential dwellings is situated on previously developed land located within the built up area boundary of Fetcham. The development that came forward remediated historic flooding issues due to the River Mole located nearby and a tributary running through the heart of the site, whilst no development took place in flood zone 3.

Amongst the significant work that has taken place on-site in order to improve the flood risk of the site and surrounding area, the coverage of impermeable surfaces has halved compared to the original site layout whilst the creation of sustainable drainage features include a large dry pond and swales to reduce surface water run-off. Existing trees and boundary screening have been retained in addition to the planting of over 100 new trees and further landscaping to boundaries which improves biodiversity and reduces the need to design in artificial flooding mitigation.

Paved surfaces

The rate of paved surfaces in front gardens of residential properties has increased in recent decades. In addition to homeowners making choices to reverse this trend, new developments should offer permeable paving where driveways are required for cars, but also make sure that where hard surfacing is necessary, it is supplemented with greener elements such as grass and planting.

This SuDS project in London uses brick paving to allow water to drain away between the gaps although careful installation onto compacted aggregate is required for this to happen.

Photo © Robert Bray Associates

The use of gravel is a cheap alternative to other forms of SuDS and with recycled products also available to use, it presents as a sustainable method for residential dwellings.

Also making use of recycled material in the form of the matrixing underneath the chosen aggregate, matrix/cellular paving is a popular choice.

Photo © SE Landscape Construction

Grass can be used to reinforce SuDS measures and provide a greener design to permeable paving, which may be a consideration if space is lacking.

The costs to developers to implement SuDS can be considered reasonable, especially when the numerous benefits they provide are taken into consideration. Efficient and effective installation of SuDS can retain between 60 to 72% of surface water runoff whilst SuDS measures such as ponds or swales can mimic the similarity of species richness found in a natural pond by up to 80%. Raingardens and soakaways typically cost £336 (£ per meter2) to install whilst ponds and swales are a tenth of the cost; maintenance costs (£ per meter2 /year) are often far less than £1, providing a cost-effective measure.

Pocket parks

Pocket parks (see page 321 of the London Plan) are smaller areas of green space, often no larger than 0.4ha that may provide seating, play equipment and water features within a natural setting offering areas both for daylight and shade. These areas have less emphasis on movement compared to other areas such as green active travel corridors or larger open spaces on the edge of urban boundaries, so other activities to increase community engagement with the space may be considered.

Case study: Church Road, Ashford (residential and mixed-use development)

The Church Road development in Ashford delivers natural elements throughout the site to create a welcoming environment within the urban setting for residents and the wider community. The new development uses a 'tree-lined shared-surface boulevard' that leads people from a high street setting, via a quieter and relaxed pocket park that is echoed in the smaller scale housing that surrounds it, through to a larger open space with additional facilities.

The Church Road development in Ashford delivers natural elements throughout the site to create a welcoming environment within the urban setting for residents and the wider community. The new development uses a 'tree-lined shared-surface boulevard' that leads people from a high street setting, via a quieter and relaxed pocket park that is echoed in the smaller scale housing that surrounds it, through to a larger open space with additional facilities.

There are further distinguishable spaces within the site, most notably the north facing raised belvedere garden for residents that overlooks the large open space, that create intrigue whilst catering for a wide user group.

Image © CZWG Architects

Green and active travel corridors

Active travel refers to modes of non-motorised transport and is most associated with walking and cycling (see the Sustrans traffic-free routes and greenways design guide). Investing in quality active travel measures that are linked to popular destinations such as high streets, local centres and greenspace will improve individuals' health and quality of life, the environment (including reducing the effects of climate change through fewer private vehicle journeys), and local productivity, while at the same time providing a more cost-effective infrastructure especially if maintenance requirements are minimised. By encouraging more local journeys that are more climate-friendly, we are able to deliver the '20-minute neighbourhood' or the '15-minute city'.

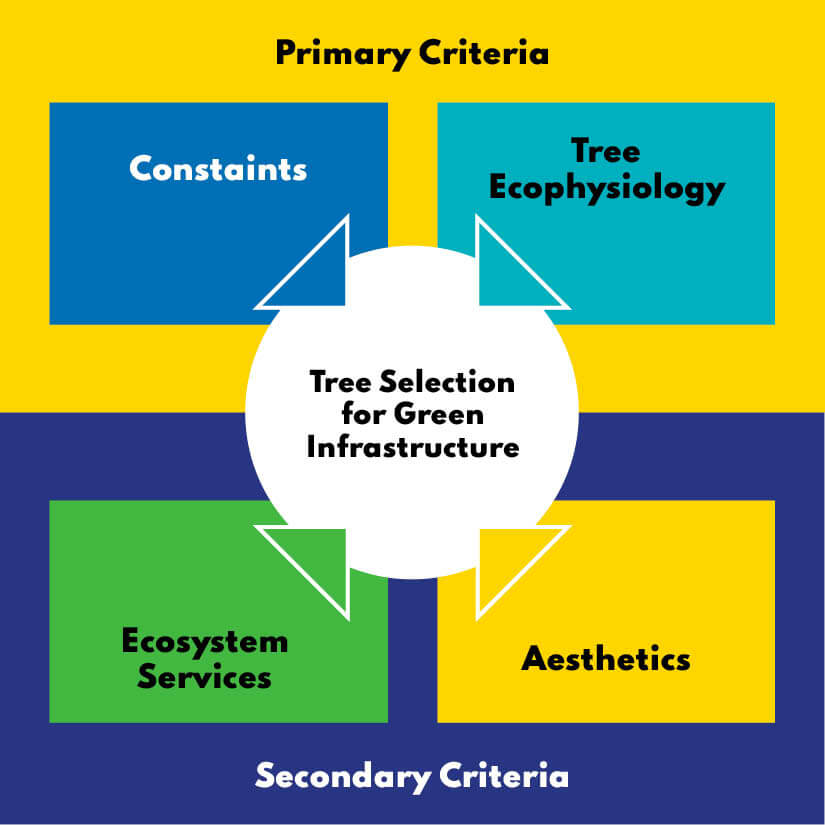

Diagram 3: The sustainable travel hierarchy

The sustainable travel hierarchy shows that walking is the most sustainable travel mode and that this should dictate our transport design decisions. After walking, the diagram shows that the priorities for travel modes are cycling/scooting, e-bikes, public transport, car clubs/taxis/car sharing, private car and least priority should be given to air.

Many larger developments in Surrey that are allocated in Local Plans are on the edge of urban settlements, thereby extending the urban boundary and the potential distances to travel to key locations. It is important that these new developments not only consider how prospective residents will move around that development, but also consider how more sustainable journeys can be made between that development and other settlements and community uses in the surrounding areas without reliance on the private car. Residents of new developments should not be faced with the private car being the only means for accessing essential facilities, such as light retail, schools and greenspaces.

The photo below is a bus stop from Mindenhurst, a new neighbourhood located in Deepcut Village. Many destinations from Mindenhurst can be accessed on foot, by bike or by public transport. The bus shelter is equipped with seating, lighting, integrated cycle parking, and will be provided with timetable and route information, and real time service information displays once new bus services serving the village become operational. It aims to marry up cycling and bus usage in the form of a 'cycle and ride' facility, making travel by bus straight forward and provide easy interchange from cycling.

New green linear corridors between existing sites in urban areas, such as rivers, road and rail corridors, active travel corridors and the rights of way network, have a distinct positive impact for species who use these corridors as travelling routes to move from one protected site to another, as well as habitats. In addition to addressing great habitat loss, better quality green routes that are traffic-free help us to make the transition towards a more climate-friendly society.

Within Surrey County Council's new Local Transport Plan 4, there is an objective to create thriving communities with clean air, excellent health, wellbeing and quality of life through more attractive built and natural environments. Success will be measured against this target by measuring the area or length of green infrastructure developed, such as greenways.

An example of one ongoing project to improve active travel in Surrey is the Surrey Strategic Greenway Initiative which seeks the provision of a high-quality walking, cycling and horse-riding network spanning the county whilst using these routes as the basis for environmental improvements. By ensuring that green and active travel corridors are delivered in reasonable proximity from people's front doors, we can start to realise a comprehensive active travel network within the county that can offer a genuine alternative transport mode to the private car.

Considerations for nature within the active travel network

When considering the role of green corridors, thought is needed as to the purpose that these corridors will serve and how the design of the corridor will serve the stated purpose, whether this is to link habitats or create corridors for species.

To achieve maximum benefits as conduits for species, green corridors need to be as wide as possible, so the impacts of disturbance and lighting are reduced, if not removed, at the edges especially where waterways are present. Any lighting present in these locations should also be designed to avoid impacts on sensitive species such as bats, nesting birds and invertebrates.

Green corridors will also need to be managed to retain their functionality as well as monitored once project delivery is complete to understand the true benefits. A well planned and managed green corridor should achieve benefits for both people and wildlife and these cannot be created by simply drawing green lines on a map. Further information can be sought from Sustrans' Greenway Management Handbook .

Corridors for movement purposes

Active travel infrastructure should target a wide array of users and it is important that the needs of as many user groups as possible are taken into consideration through targeted public consultation when designing or improving new corridors. Each active travel corridor and greenway differs from the next, so it is important that the context of the route is understood and who it will cater for. Some users will prioritise getting from A to B quickly and efficiently as part of a commute. For others, taking journeys to community spaces such as schools and libraries as well as places of community interest along the route itself, such as natural play spots, is an important aspect.

The design principles for movement corridors can be found in guidance documents such as the National Design Guide, Manual for Streets 1 and Manual for Streets 2 as well as the Healthy Streets for Surrey Design Guide. Surrey County Council, as the Local Highways Authority for Surrey, would expect travel plans for new development to incorporate active travel measures and show how the development reduces the reliance on the private car." In terms of green and blue infrastructure, Transport for London have introduced the '5Cs of Good Walking Networks (see p. 26 of Planning for Walking)' that should be followed when thinking about planning for active travel infrastructure. It should be:

- Connected: routes should link to key attractors such as bus stops and schools, whilst connecting locally and at a district level to form a wider network.

- Convivial: routes and public spaces should be pleasant, safe and enriched by multiple activities.

- Conspicuous: routes should be clear to follow with waymarking including street names and numbers.

- Comfortable: surfaces should be of high quality that drain easily and routes should be quiet and away from noise and traffic where possible. Opportunities for rest and shelter should be provided.

- Convenient: routes should be direct and prioritise pedestrians of all groups and ability.

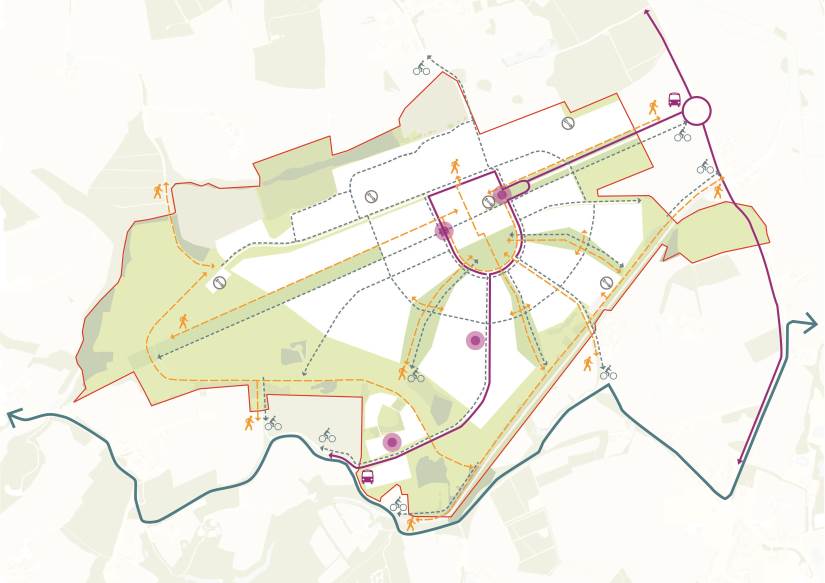

These principles are universally known and are being used in practice, as can be seen in the below map that shows how active travel planning could be approached at the masterplan stage. The Dunsfold Garden Village Supplementary Planning Document shows how a network of vehicle free walking and cycling routes will connect neighbourhoods and destinations within and beyond the site, making use of the retained peri-track (from former airfield operations), the proposed new canal towpath, and more local routes across the green wedges and landscape.

Diagram 4: An example of active travel measures planned as part of a wider masterplan

Diagram © Allies and Morrison, 2022

Active travel infrastructure should also draw on other measures outlined in this document, to ensure that it can continue to be used and does not require additional maintenance. The use of SuDS located close to the street network will ensure that walking and cycling is not interrupted by seasonal flooding whilst although appropriately chosen trees and planting are preferred to blank surfaces like walls and fences, these should minimise the chance of active travel routes becoming overhung or damaged by tree roots.

Case study: New Malden to Raynes Park traffic-free movement corridor

The new active travel corridor linking New Malden to Raynes Park provides a combination of 'corridors for movement purposes' and 'corridors for nature and recreational purposes'.

The 1.2 kilometres long traffic-free path delivers a wide active travel network with green improvements that allows users to travel between two popular towns whilst avoiding busy roads and dual carriageways. For those in less of a hurry, the images below show that there are play spaces such as rope swings and 'stepping stones', information posts to identify trees and places to rest amongst the flora and fauna that encourage both activity and intrigue.

Corridors for nature and recreational purposes

For other corridors, quick and efficient movement may not be the primary issue and instead, design for socialising and recreation will be more important. As has been explained, we require green and blue spaces such as the larger, more consolidated destinations such as parks or playing fields to be linked together via a multifunctional network of green and blue corridors.

These longer and more continuous corridors of green and blue space however can themselves be places of rest and relaxation and fulfil a more local and daily requirement for time spent outdoors. Such spaces create intrigue and allow recreational walkers to meander and create their own routes. These spaces are also able to be retrofitted to existing urban environments where space permits.

Simple infrastructure installations such as this walkway encourage residents and all visitors to explore the site.

Photo © Robert Bray Associates

New developments should make every opportunity to link to existing green spaces. To avoid an isolated area developing, a development could incorporate a continuous green route through it that links to a wider network at each end. Should this not be possible, a series of smaller sites in close proximity could act as stepping stones and contribute towards biodiversity net gain.

When designing or enhancing long corridors or linear green 'patches', accessibility for as many residents as possible is necessary if they are to be successful. By engaging with local residents along planned or improved corridors, schemes stand a greater chance of being used and maintained. As set out in Natural England's Accessible Natural Green Space Standards, the ideal distance from these corridors in order for them to be deemed accessible is 400 meters or 10 minutes. Green and active travel corridors can be used to link peri-urban and extra-urban areas to one another, improving route options for nature as well as humans.

Case study: Church Street and Paddington Green infrastructure and public realm plan, Westminster

The Church Street and Paddington Green area has been recognised as an area in need of regeneration by Westminster City Council, for reasons including poor air quality, deficient open space for play and contact with nature and poor physical and mental health. Through it's ownership of much of the land in the area, Westminster has commenced plans to connect existing green spaces and gardens via green streets and public spaces that will include market areas, informal play spots, gardens, spaces for wildlife. Much of the redevelopment of corridors will be car-free routes.

Case study: The Hoe Valley regeneration project, Woking

The Hoe Valley project has greatly improved biodiversity and reduced the flood risk element for many nearby residents. But unlike its previous industrial use, it has also become a place for visitors to spend time and explore via active travel means.

The enhanced green and blue infrastructure on site have contributed to a visual attraction and has led to a far more pleasant site for the local community to enjoy. Cycle paths and walking routes have been provided that are separated from road traffic whilst construction of one new road bridge with the addition of a replacement pedestrian bridge that is now Disability Discrimination Act (DDA) compliant has also been achieved. Play areas have been created to accompany the new housing development and new seating, picnic benches and litter bins have been placed throughout the site.

The scheme has involved the local community throughout with newsletters, presentations and media days organised. Existing paths remained open during the construction phase to allow individuals to continue to use routes that were quick and familiar.

Planting and an accessible gravel walkway delivered as part of the Hoe Valley regeneration project

Photo © ThamesWey

Green links from urban to rural

Surrey does not have any cities and is one of the least deprived areas in the country, with many residents having access to good quality public greenspace and experiencing better health outcomes than elsewhere. However, there are areas of deprivation in Surrey and the Marmot Review 10 Years On highlighted that for those living in these areas throughout the UK, health is getting worse and health inequalities are increasing.

This section is therefore concerned with how to maximise the use of our countryside, open spaces and green areas on the periphery of our urban boundaries for the enjoyment of all without impacting the sustainability of such areas. This guide is primarily concerned with increasing natural capital in our urban areas and this aim is supported when we increase the flow of nature from rural areas beyond the urban boundary into our towns.