As the nation honours the sacrifice made by so many in two world wars and other conflicts, our November Marvel looks at the impact of the Great War on a young officer who recorded his experiences in letters to his parents and brother. Although he survived, his experiences and the losses he endured marked him profoundly.

As the nation honours the sacrifice made by so many in two world wars and other conflicts, our November Marvel looks at the impact of the Great War on a young officer who recorded his experiences in letters to his parents and brother. Although he survived, his experiences and the losses he endured marked him profoundly.

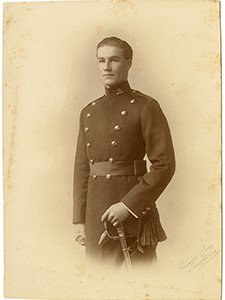

Guy Olliver was a young officer in the Queen's Royal West Surrey Regiment and his letters home were recently placed in our care, written to his parents and, chiefly, to his brother in the Royal Navy. As an officer, Olliver censored his own letters and though they are often short, written in pencil on whatever scraps of paper were to hand, they are very revealing of his state of mind and hopes and fears for the future.

Olliver was born on 20 July 1892 and, after officer training at Sandhurst, joined the Queen's West Surreys as a second lieutenant in 1912. Before the war he spent two thoroughly enjoyable years with the 2nd Battalion in Bermuda and South Africa and anticipated serving with the battalion in France but instead was attached as an officer to the-newly formed 7th Cyclist Company, 7th Division. The mechanised slaughter on the western front came as a terrible shock to him. In October 1914 he wrote that he had seen things 'I never wish to see again' and was particularly disturbed by the impact of artillery shells, reducing men to 'ham'. At that point he was optimistic that the Allies would be in Berlin by Christmas and that Germany's capacity to sustain the war effort would soon be exhausted, but these hopes soon faded.

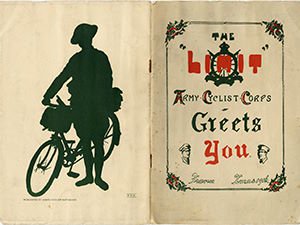

The cyclists generally enjoyed better billets than the troops in the front line, and the spring and summer of 1915 saw him playing cricket and croquet in a delightful rural billet with a charming 'mademoiselle'. However, conditions during the bleak winter months increasingly depressed him. His attitude to the enemy hardened very quickly and soon he was suggesting that sailors of sunk German ships should not be rescued and that U-Boat crews should be hanged when the war was over.

The cyclists generally enjoyed better billets than the troops in the front line, and the spring and summer of 1915 saw him playing cricket and croquet in a delightful rural billet with a charming 'mademoiselle'. However, conditions during the bleak winter months increasingly depressed him. His attitude to the enemy hardened very quickly and soon he was suggesting that sailors of sunk German ships should not be rescued and that U-Boat crews should be hanged when the war was over.

He gives a vivid account of the battle of Loos in September 1915, when he was sent to the front to see how far the infantry had advanced and found himself frantically pedalling along a road lined with Germans taking pot shots at him, 'hitting my poor old bike in several places, puncturing both wheels and breaking the spokes' before finally wounding him in the calf. He managed to escape on foot, though had to leave behind his mud-clogged bike, new Burberry overcoat and a shaving kit.

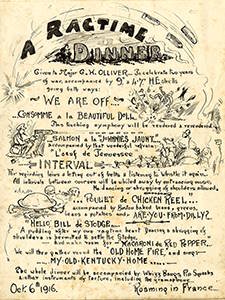

The carnage profoundly affected him. In April 1916, now in command of the 32nd Division's cyclists, he wrote that the war had drained him of all happiness and that 'one plods on without looking into the future'. By this point he had lost all the friends he had admired, and his brother was 'the only pal I have got now'. He could not help looking back on his idyllic childhood and the carefree early days of his military career. Though still convinced that the Germans would ultimately lose the war, he admired their resolution. They were, he felt, 'a wonderful nation for doing things. They don't sit and talk like we do'.

The carnage profoundly affected him. In April 1916, now in command of the 32nd Division's cyclists, he wrote that the war had drained him of all happiness and that 'one plods on without looking into the future'. By this point he had lost all the friends he had admired, and his brother was 'the only pal I have got now'. He could not help looking back on his idyllic childhood and the carefree early days of his military career. Though still convinced that the Germans would ultimately lose the war, he admired their resolution. They were, he felt, 'a wonderful nation for doing things. They don't sit and talk like we do'.

Leave at the beginning of 1917 allowed him to visit the new family home at Hatchgate, Horley, but also enjoy Walter Ellis's play 'A Little Bit of Fluff' at the Criterion Theatre, along with dances at the Savoy and a Turkish bath. A thoughtful, sensitive man (except where killing Germans was concerned), in February 1918 we find him filling the long winter months uneasily anticipating a great German offensive and also 'studying social problems for after the war' as he was convinced that something would need to be done to improve the lot of the working classes to avoid 'a great upheaval'. The German offensive duly materialised and took the lives of more of his old regimental pals, leaving him the only survivor of the 2nd Battalion's officers still serving in France. He could not help reflecting to his brother, now safe in a shore job, that 'we are wasting the best part of our lives'.

In July 1918 he was given temporary command of the 1st Battalion of the Queen's, a great honour he felt, but his pride was short-lived when in October he was demoted because a mustard gas attack caused many casualties as his men were late in putting on their gas helmets. He was left 'shaken but not broken' and attributed his demotion to a 'stinking fish' of a brigadier who disliked him. He later reflected that he had had a fortunate escape as since his departure from 1st Battalion, three successive commanders had been killed or wounded. When the armistice was signed, he was a company commander with 6th Battalion, the Queen's, with the task of training more raw recruits, but the ceasefire allowed him to reflect to his brother that 'you and I have a lot to congratulate ourselves on and we will celebrate getting through the war when I get home'.

In July 1918 he was given temporary command of the 1st Battalion of the Queen's, a great honour he felt, but his pride was short-lived when in October he was demoted because a mustard gas attack caused many casualties as his men were late in putting on their gas helmets. He was left 'shaken but not broken' and attributed his demotion to a 'stinking fish' of a brigadier who disliked him. He later reflected that he had had a fortunate escape as since his departure from 1st Battalion, three successive commanders had been killed or wounded. When the armistice was signed, he was a company commander with 6th Battalion, the Queen's, with the task of training more raw recruits, but the ceasefire allowed him to reflect to his brother that 'you and I have a lot to congratulate ourselves on and we will celebrate getting through the war when I get home'.

After the war Olliver returned to 2nd Battalion, serving in India and Sudan, before commanding the Queen's Depot in Guildford between 1931 and 1934. He would probably have taken over command of 2nd Battalion but died on 10 August 1936 aged only 44.

See also

- The Queen's Royal Surrey Regiment

- Researching a soldier, sailor or airman who served in the First World War

Images

Select image to view a larger version.

- Guy Olliver as a young officer (reference 10639/3/1)

- Guy Olliver (back row, left) on the western front (reference 10639/3/3). Link as above.

- Programme for a 'ragtime dinner' for Olliver to mark two years of war, 1916 (reference 10639/2/1)

- Cover of the magazine of the Cyclist Corps, December 1916 (reference 10639/2/2)