When George Alan Brodrick succeeded his father to the title of Viscount Midleton it was in somewhat awkward circumstances. The two had fallen out badly, George having first dropped out of Cambridge and then compounded his error by marrying Ellen Griffiths, a laundry maid, to the great delight of gossip columnists. When he moved into the family seat at Peper Harow in 1836, as the 5th Viscount, he found that his father had ensured that he had inherited 'the bare walls …. had not a bed to sleep in, a chair to sit down on or saucepan to boil in'. Not only that, but polite society wanted nothing to do with the new Viscount and his humble wife. Shunned by his peers, he instead threw his energies into transforming and adorning his Peper Harow estate. To modify the Classical mansion house, he employed Charles Cockerell, but for all his other building projects his architect was the fiery, excitable and controversial Augustus Welby Pugin, a Catholic convert. It should have been a marriage made in heaven as the Viscount and Pugin were both firm believers that the Gothic was the only style suitable for Christian architecture and eager to create buildings that revived the craftsmanship and colour of the Middle Ages.

When George Alan Brodrick succeeded his father to the title of Viscount Midleton it was in somewhat awkward circumstances. The two had fallen out badly, George having first dropped out of Cambridge and then compounded his error by marrying Ellen Griffiths, a laundry maid, to the great delight of gossip columnists. When he moved into the family seat at Peper Harow in 1836, as the 5th Viscount, he found that his father had ensured that he had inherited 'the bare walls …. had not a bed to sleep in, a chair to sit down on or saucepan to boil in'. Not only that, but polite society wanted nothing to do with the new Viscount and his humble wife. Shunned by his peers, he instead threw his energies into transforming and adorning his Peper Harow estate. To modify the Classical mansion house, he employed Charles Cockerell, but for all his other building projects his architect was the fiery, excitable and controversial Augustus Welby Pugin, a Catholic convert. It should have been a marriage made in heaven as the Viscount and Pugin were both firm believers that the Gothic was the only style suitable for Christian architecture and eager to create buildings that revived the craftsmanship and colour of the Middle Ages.

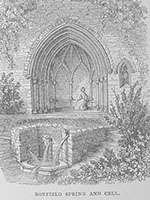

Midleton first commissioned Pugin to build for him an imposing gatehouse and farm buildings at the Oxenford entrance to Peper Harow Park. We have a sketch which Pugin drew for his patron to demonstrate how the Oxenford buildings would look from the road. Close by he also designed a delightful Gothic fountain and hermitage at Bonfield Spring, reputed to be a medieval holy well with healing properties. The vivid letters from architect to viscount discuss materials, prices, details and labour and document what proved to be a tempestuous relationship. Midleton, even his friends acknowledged, was a difficult man and Pugin was never afraid to give vent to his many strongly-held opinions. When Midleton suggested that local builders were used for the Oxenford farm buildings instead of Pugin's own favourites, the architect retorted that he certainly would not employ 'modern humbugs of builders' and went on, 'I have not the least wish of intruding my services on any one, nor would I wish to be employed unless I have the full confidence of those for whom I build. God knows, I am deserving of it'.

Midleton first commissioned Pugin to build for him an imposing gatehouse and farm buildings at the Oxenford entrance to Peper Harow Park. We have a sketch which Pugin drew for his patron to demonstrate how the Oxenford buildings would look from the road. Close by he also designed a delightful Gothic fountain and hermitage at Bonfield Spring, reputed to be a medieval holy well with healing properties. The vivid letters from architect to viscount discuss materials, prices, details and labour and document what proved to be a tempestuous relationship. Midleton, even his friends acknowledged, was a difficult man and Pugin was never afraid to give vent to his many strongly-held opinions. When Midleton suggested that local builders were used for the Oxenford farm buildings instead of Pugin's own favourites, the architect retorted that he certainly would not employ 'modern humbugs of builders' and went on, 'I have not the least wish of intruding my services on any one, nor would I wish to be employed unless I have the full confidence of those for whom I build. God knows, I am deserving of it'.

Pugin then moved on to transform St Nicholas' church near the family seat. Out of the humble, austere little building, he constructed a medieval extravaganza, suspiciously colourful and ornate to Protestant eyes, with an elaborate Norman chancel arch, an Early English style north arcade, a Decorated style chancel and a mortuary chapel designed to contain Midleton's tomb on the north side of the chancel. The combination of architectural styles was intended to give the impression of a building that had evolved over several centuries. The Midleton crest and initial were everywhere: on the floor tiles, on the wooden ceilings, on the metal screen and in the stained glass, described by Pevsner as 'excitable'. A new tower and spire were also planned but never erected.

Pugin then moved on to transform St Nicholas' church near the family seat. Out of the humble, austere little building, he constructed a medieval extravaganza, suspiciously colourful and ornate to Protestant eyes, with an elaborate Norman chancel arch, an Early English style north arcade, a Decorated style chancel and a mortuary chapel designed to contain Midleton's tomb on the north side of the chancel. The combination of architectural styles was intended to give the impression of a building that had evolved over several centuries. The Midleton crest and initial were everywhere: on the floor tiles, on the wooden ceilings, on the metal screen and in the stained glass, described by Pevsner as 'excitable'. A new tower and spire were also planned but never erected.

Midleton then decided, as part of his plans to modernise his town of Midleton and associated estates in County Cork, Ireland, that Pugin should design a series of buildings to act as an ornament and inspiration. But the relationship between the two of them swiftly deteriorated beyond repair. Midleton thought Pugin's plans too extravagant to which the angry architect retorted that it was hard 'to design and build such cheap and common buildings after always aiming to make good things' and lamented, 'all I do for you in England is a delight and an honour, but these Irish farm buildings are intolerable'. Pugin had recently lost his wife. He was depressed and hated the long journeys to Ireland to work on buildings he thought unworthy of his talents: 'I could be producing works of art while I am writing about potato sheds'. Shortly after, Midleton cut off all communication with the architect, with little accomplished.

Midleton then decided, as part of his plans to modernise his town of Midleton and associated estates in County Cork, Ireland, that Pugin should design a series of buildings to act as an ornament and inspiration. But the relationship between the two of them swiftly deteriorated beyond repair. Midleton thought Pugin's plans too extravagant to which the angry architect retorted that it was hard 'to design and build such cheap and common buildings after always aiming to make good things' and lamented, 'all I do for you in England is a delight and an honour, but these Irish farm buildings are intolerable'. Pugin had recently lost his wife. He was depressed and hated the long journeys to Ireland to work on buildings he thought unworthy of his talents: 'I could be producing works of art while I am writing about potato sheds'. Shortly after, Midleton cut off all communication with the architect, with little accomplished.

The affairs of the mercurial and depressive viscount himself were now slipping into turmoil. The potato blight which ravaged Ireland from 1845 devastated Midleton's estates and income and his flirtatious liaison with a Suffolk lady called Frederica Rushbrooke caused the long-suffering Ellen Lady Midleton to flee Peper Harow. On Tuesday 31 October 1848, Midleton dined late and alone in the great mansion. After fortifying himself with alcohol, he removed his shoes and went with a candle to a small room where a brazier stood for drying out damp wallpaper. A servant found him dead the following morning, lying on the floor, his head on a pillow, having asphyxiated himself. His fifth and last will lay close by with a letter addressed to Miss Rushbrooke, to whom he had left much of his fortune. When he heard the news, Pugin was not surprised: 'That unhappy man Lord Midleton has at last destroyed himself. I gave up all hopes of him when he put up the old pews in the new aisle I built for him. I thought he would come to a miserable end'. At the inquest, which recorded a verdict of suicide while the mind was disturbed, the Vicar of Peper Harow observed that 'had I been asked who I thought the most unhappy man in the world, I should unhesitatingly have said Lord Midleton'.

The buildings in Peper Harow still stand as testimony to the brief, tumultuous but productive partnership of aristocrat and architect. The Oxenford gatehouse is now available to let as a holiday home through the Landmark Trust, but sadly water no longer flows through the Bonfield spring fountain, lost in surrounding woodland. St Nicholas' church was badly damaged by a fire on Christmas Eve 2007, but much of Pugin's work survived and it has now been restored. Outside the east end of the church can be found the grave of the 5th Viscount, surrounded by his kin, many of whom had shunned him when alive.

Images

Select image to view a larger version.

- Peper Harow house, showing Charles Cockerell's alterations, including the balustrade and coat of arms and the porch (reference PX/115/5/2)

- Pugin's sketch of the Oxenford gatehouse, barn and farm buildings (reference 1248/26/1)

- The completed Oxenford buildings as depicted in E W Brayley 'A Topographical History of Surrey', volume 5 (1848)

- Pugin's hermitage and fountain at Bonfield Spring as depicted in E W Brayley 'A Topographical History of Surrey', volume 5 (1848)