Prior to 1834, the parish was the key unit in the administration of the poor law, a responsibility that dated back to the late 16th century. By 1731, Chertsey and Croydon had established parish poor houses and, later, Woking's Poor House would have space for 40 paupers. In 1782, the Relief of the Poor Act (also known as the Gilbert Act) was passed which allowed parishes to share the cost of looking after the poor by combining to establish a common workhouse. However, it was the Poor Law Amendment Act of 1834 that created Union workhouses, one of the most infamous icons of Victorian Britain. By the Act, parishes were grouped into Poor Law Unions with each new workhouse serving all the parishes within its Union. Surrey would have ten Union workhouses which were not just for the poor, but also the elderly, children whose families could no longer look after them, and the sick.

Prior to 1834, the parish was the key unit in the administration of the poor law, a responsibility that dated back to the late 16th century. By 1731, Chertsey and Croydon had established parish poor houses and, later, Woking's Poor House would have space for 40 paupers. In 1782, the Relief of the Poor Act (also known as the Gilbert Act) was passed which allowed parishes to share the cost of looking after the poor by combining to establish a common workhouse. However, it was the Poor Law Amendment Act of 1834 that created Union workhouses, one of the most infamous icons of Victorian Britain. By the Act, parishes were grouped into Poor Law Unions with each new workhouse serving all the parishes within its Union. Surrey would have ten Union workhouses which were not just for the poor, but also the elderly, children whose families could no longer look after them, and the sick.

To enter one of these workhouses a person or family had to be interviewed either by the Union's Relieving Officer, the Master of the Workhouse or the Board of Guardians. If approved, they would be issued with a letter or a printed form which had to be presented at the workhouse within six days. Once at the workhouse, they would be stripped, bathed, examined by the medical officer and issued with a uniform, then sent to the Receiving or Probationary Ward. A pauper would also be placed in a 'class', according to their gender, status and age. Families were also often segregated between female and male wards.

An exception to this was vagrants who came from outside the workhouse's catchment area. They had to queue outside the Casual Ward or 'Spike' from early evening. If granted entry, they would be searched for any alcohol and then given a bath, a nightshirt and some gruel (porridge made with water) and bread. They were often only allowed to stay at the workhouse for a night or two before being sent on their way early the following morning. In return for their bed and board they would have to complete a set amount of work, such as breaking up stones or unravelling old rope for oakum.

An exception to this was vagrants who came from outside the workhouse's catchment area. They had to queue outside the Casual Ward or 'Spike' from early evening. If granted entry, they would be searched for any alcohol and then given a bath, a nightshirt and some gruel (porridge made with water) and bread. They were often only allowed to stay at the workhouse for a night or two before being sent on their way early the following morning. In return for their bed and board they would have to complete a set amount of work, such as breaking up stones or unravelling old rope for oakum.

In theory, inmates were not allowed to leave the workhouse, except for specific reasons such as looking for work. If a person wished to discharge themselves then they had to give 'reasonable notice'. Their clothes would be returned to them, but if they later wanted to be readmitted then they would have to go through the admission process all over again.

In 1929, under the Local Government Act, Poor Law Unions were abolished and responsibility for the poor passed to County Councils. In 1948, the National Health Service took over many former workhouse hospitals.

In 1929, under the Local Government Act, Poor Law Unions were abolished and responsibility for the poor passed to County Councils. In 1948, the National Health Service took over many former workhouse hospitals.

For more information about the Poor Law and Board of Guardians records held at Surrey History Centre, see our Poor Law Records research guide.

Peter Higginbotham's The Workhouse website and W E Tate's book, The Parish Chest, are useful resources.

The Guildford Spike Vagrants and Casuals Ward (built in 1906 as part of Guildford Workhouse) was restored in 2008 and now houses a museum, The Spike Heritage Centre, giving a fascinating insight into life in these institutions.

Images

Select image to view a larger version.

- Extract of punishments for inmates of the workhouse (reference P30/7/583)

- 50" to 1 mile Ordnance Survey map, showing the layout of Guildford Workhouse, 1871 (Ordnance Survey reference XXIV.13.21)

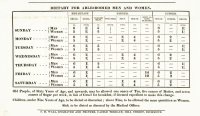

- Chart showing the diet of paupers from Mortlake parish records, 1836 (reference 2414/6/607)