Overview and context

This guidance seeks to complement Policy 7 (Safeguarding) of the Surrey Waste Local Plan 2020 by providing context for the importance of and need for the safeguarding of waste management facilities in the county.

Surrey

The largely rural county of Surrey comprises 11 districts and boroughs (and 12 Local Planning Authority plan-areas) and is bounded by six other counties and Greater London. It measures about 1,660 square kilometres and, with some 1.2 million residents, is a popular place to live, work, and visit. Surrey is one of the most densely populated shire counties in England with 481,800 households of which 87% are in urban areas and 13% in rural areas.

SCC's Organisation Strategy 2023 to 2028 sets out that Surrey's economy is worth £43.5 billion with a high (and increasing) proportion of large businesses and a 25% higher business density than the national average. Residents have average full-time earnings of £38,418 per annum (pa), about £7,000 above the national average.

A key contributor to Surrey's economic success is its unique strategic location. It abuts the UK's two major international airports (Heathrow and Gatwick) and is close to London and other economically successful areas such as the Thames Valley and M3 corridor. It also has good road and rail access to London and the south coast with nationally significant roads (M25, M3, M23, A3, A24, A25, A31) routing through the county.

The need for a productive economy is important for Surrey's local communities. The county is an important growth, innovation and exporting powerhouse for the UK and investment in Surrey is critical if the county is to maximise its contribution to the country's economic recovery and long-term sustainable growth.

Population projections (2018 to 2043) by the Office for National Statistics show that in 2020 there were 1,196,236 Surrey residents and this is forecast to increase by 2.6% to 1,227,467 in 2043. Surrey's 2050 Place Ambition identifies that net housing completions in the county were 5,100 in 2021/22 (up from 4,600 in 2020/21), but this is below the need figure of over 5,600 new homes a year.

Surrey also benefits from a diverse array of landscapes and hosts a variety of habitat types. Geology, landform, land-use, and climate combine to determine the characteristics of different parts of the county such as heathland, woodland, and chalk grassland. Over 70% of the county has one or more national or international landscape or nature conservation designations including 2 National Landscape Designations (Surrey Hills and High Weald); 2 wetlands of international importance (Ramsar sites); 2 Special Protection Areas; 3 Special Areas of Conservation; 65 Sites of Special Scientific Interest; 3 National Nature Reserves; 7 Biodiversity Opportunity Areas, and nearly 800 Sites of Nature Conservation Importance.

Surrey is also the most wooded county in England with about 23% of it being covered by woodland of which about 120 square kilometres is irreplaceable Ancient Woodland. Some 73% of the county is designated Metropolitan Green Belt and it also hosts a network of some 3,482 kilometres (km) (about 2,164 miles) of footpaths, bridleways, and byways.

Surrey's unique strategic position, its excellent road and rail connectivity, its highly skilled workforce, diverse and increasingly digital business base, its world class education facilities, and its quality environment are all valuable and prized assets. However, the very assets that make Surrey such an attractive place are the ones that give rise to fierce competition for land and present challenges, particularly in the context of this guidance, to safeguarding the county's existing waste management facilities.

Waste

Owing to its increasing population, strategic location, strong economy, and being a popular place to live, work and visit, Surrey is expected to generate around 3.4 million tonnes of waste per year by 2042. This waste will need to be managed responsibly and in the most sustainable way.

Figure 1. Forecast Waste Management Requirements in Surrey in Tonnes at Milestone Years for All Principal Waste Streams

(Surrey County Council Waste Capacity Need Assessment 2023: Capacity Gap Report, Table 14; Hazardous Waste Report, Table 5)

All Waste Arisings

| 2021 | 2026 | 2031 | 2036 | 2042 | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3,277,300 | 3,322,109 | 3,324,808 | 3,348,478 | 3,377,047 | 16,649,742 |

Section 336 of the Town and Country Planning Act 1990 and Article 3(1) of Directive 2008/98/EC of The European Parliament and of The Council say that 'waste' is any substance or object which the holder discards or intends or is required to discard.

All development generates waste. It arises from differing sources including land clearance and engineering operations, ground excavations, demolition of structures, construction activities, and occupation and use of land and buildings. The volume or amount of waste generated by any development will depend on a range of variables including its scale, and whether it is permanent or temporary, or domestic, commercial, or industrial in nature.

There are a range of waste types, and different types of waste can be mixed. However, for land-use planning purposes waste falls within five principal categories:

- Construction, Demolition and Excavation Waste (CD&E waste).

- Commercial and Industrial Waste (C&I waste).

- Local Authority Collected Waste (LACW).

- Hazardous Waste.

- Other Waste.

CD&E waste comprises material resulting from the construction or demolition of buildings, ground excavations, or engineering operations.

C&I waste arises from the use of land and buildings for commercial and/or industrial purposes including restaurants, hotels, cafes, trade businesses, and offices.

LACW comprises material arising from households and collected by District and Borough Councils (Waste Collection Authorities) including food waste, plastic and metal, and black bag waste.

Hazardous waste poses a threat to human health and the environment because it is toxic, flammable, corrosive, and/or carcinogenic. It arises from different sources so does not occur as a discrete waste stream.

Other Waste comprises wastewater from land and buildings and sewage sludge arising from the treatment of wastewater by utility companies such as Thames Water. It also includes organic waste produced on farms as part of the farming process (such as slurries and manure). This waste falls outside the scope of 'controlled waste' although regulation is applied through other means. Low-level radioactive waste, also included in the 'other waste' category, arises in a range of settings including hospitals, pharmaceutical and research (universities, colleges etc.) establishments, contaminated land, and at oil and gas wells where drilling mud may be radioactive at a low-level.

All waste is held, stored, transferred, deposited, and processed in various ways and at different stages by one or more waste management facilities. The National Planning Practice Guidance, which supports preparation and implementation of waste planning policy, provides a general but non-exhaustive list of what waste management operations include:

- Metal recycling sites.

- Energy from waste incineration and other waste incineration.

- Landfill and land raising sites (such as soils to re-profile golf courses).

- Landfill gas generation plant.

- Pyrolysis/gasification.

- Material recovery/recycling facilities.

- Combined mechanical, biological and/or thermal treatment.

- In-vessel composting.

- Open windrow composting.

- Anaerobic digestion.

- Household civic amenity sites.

- Transfer stations.

- Wastewater management.

- Dredging tips.

- Storage of waste.

- Recycling facilities for construction, demolition, and excavation waste.

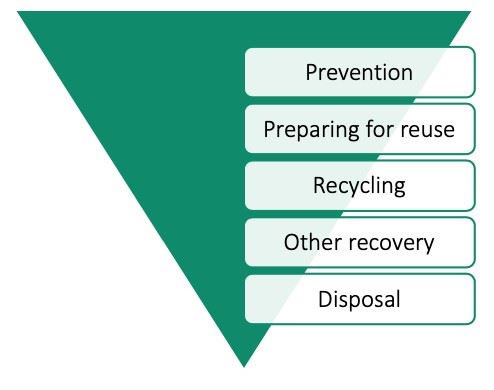

The waste hierarchy

In England, the waste hierarchy is both a guide to sustainable waste management and a legal requirement enshrined in law through the Waste (England and Wales) Regulations 2011. The hierarchy ranks differing ways of managing waste according to what is best for environmental outcomes.

Figure 2. The Waste Hierarchy

Prevention is the best and most efficient way of managing waste. It means using less material in design and manufacture, keeping products in use for as long as possible, and using less hazardous material or substances.

Second order of preference is checking, cleaning, repairing, refurbishing, and reusing whole items or parts of items in other ways.

This is followed by recycling waste to turn it into a new substance or product for example turning food and garden waste into compost or soil-type products for horticulture, or waste from building or demolition operations into recycled aggregate for making concrete.

Next is other recovery, where waste is used for beneficial purposes instead of recycling it. This could be using discarded soil and earth from ground excavations to facilitate engineering operations or incinerating left-over black bag waste collected from households or offices to generate energy for heat or electricity.

The last and least preferred way of managing waste is through disposal. However, disposal of some waste continues to be necessary as it cannot be managed in any other way including by recycling or recovery for beneficial purposes. This type of waste is commonly referred to as 'residual waste' i.e., waste left over from other treatment processes.

Climate change

The Climate Change Act 2008 (2050 Target Amendment) includes a statutory target to secure a reduction in the United Kingdom's (UK) carbon dioxide levels by 100% below 1990 levels by 2050. It also requires the UK Government to set legally binding carbon budgets for each five-year period to 2050, of which those legislated to date run until 2037 through the sixth carbon budget.

The Climate Change Committee sets out in their Sixth Carbon Budget Advice, Methodology and Policy report that the UK's sixth carbon budget, the legal limit for UK net emissions of greenhouse gases over the years 2033-37, requires a reduction in UK emissions of 78% by 2035 relative to 1990, a 63% reduction from 2019.

It also explains that although waste sector emissions in the UK have fallen 46% over the period 2008-2018 (and by 61% against 1990 levels), progress has stalled. It goes on to set out that total waste sector emissions increased by 3.7% from 2017 to 32.9 metric tonnes of carbon dioxide-equivalent in 2018 and explains that this is primarily due to the volumes of residual waste that end up in landfills or energy from waste facilities, and emissions associated with wastewater treatment. As of 2018, waste sector emissions accounted for 6% of total UK greenhouse gas emissions.

The UK Green Building Council (UKGBC)'s Net Zero Whole Life Carbon Roadmap sets out that the built environment is responsible for some 25% of UK carbon emissions, of which about 25% is embodied emissions of buildings and other infrastructure. UKGBC also reports on their website that construction, demolition, and excavation account for 60% of material use and waste generation in the UK.

Surrey's 2050 Place Ambition explains that carbon emissions are falling in the county, but not quickly enough to meet 2050 net zero emissions targets. At current levels emissions from transport in Surrey are expected to increase slightly. Currently, 46% of Surrey's emissions come from the transport sector, with housing responsible for 28% of emissions, public/commercial buildings 15%, and industry 11%.

In this context, Section 182 of the Planning Act 2008 places a duty on planning authorities to include policies that contribute to climate change mitigation and adaptation in their local plans. This would include robust land-use planning strategies and policies that prioritise and emphasise the importance of managing waste in accordance with the waste hierarchy, and safeguarding waste management facilities.

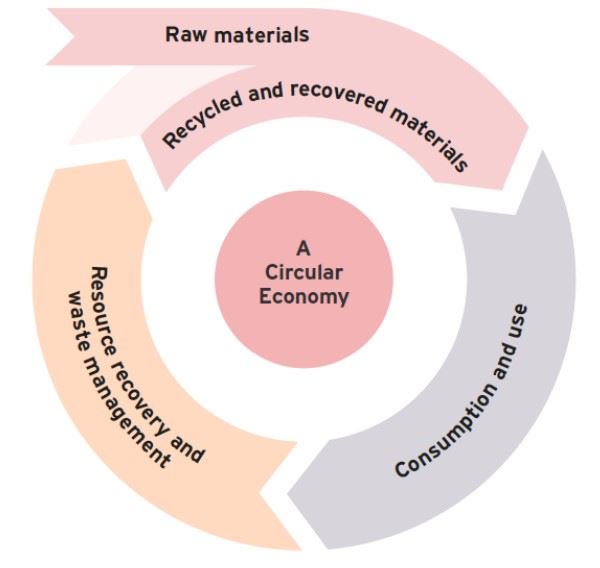

Circular economy

Fundamental to mitigating and adapting to a changing climate is moving towards a circular economy. A circular economy is an alternative to a traditional linear economy (make, use, and dispose) and an economic model where we keep resources in use for as long as possible extracting the maximum value from them whilst in use before they are recovered and regenerated at the end of their service life.

Figure 3. Circular Economy

The Waste Management Plan for England (2021) and the Waste Prevention Programme for England: Maximising Resources, Minimising Waste (2023) both seek to facilitate a circular economy by encouraging people and businesses to use products for longer, repair broken items, and enable reuse of items by others. This is particularly relevant to the e-waste generated by UK households and businesses, which may become the world's largest e-waste contributor as early as 2024 according to a recent Resource. Co article.

By designing out waste and pollution, keeping products and materials in use for as long as possible, and regenerating rather than degrading natural systems, the circular economy represents a powerful contribution to combating climate change and enhancing our environment. With increasing prices of construction material and waste disposal, embracing a circular economy would also increase business competitiveness, stimulate innovation, create jobs, and ultimately boost economic growth.

The transition to a net zero economy requires a comprehensive approach to waste management, as inefficiencies throughout the waste lifecycle contribute significantly to greenhouse gas emissions. Production processes, consumption patterns, and disposal methods all generate emissions, making waste reduction, reuse, and recycling central tenets of any effective climate change strategy.

Prioritising the waste hierarchy not only minimizes the environmental footprint of resource extraction and production but also diverts organic waste from landfills, preventing the release of potent methane. By fostering a circular economy that prioritizes resource recovery and minimizes reliance on virgin materials, sustainable waste management plays a critical role in achieving the UK government's ambitious net zero targets.

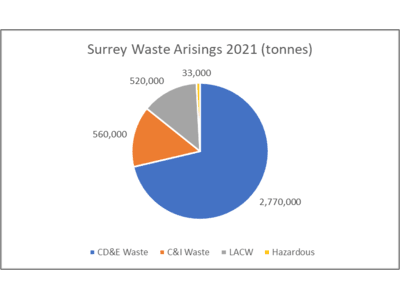

Surrey's waste

As set out in SCC's Authority Monitoring Report 2022, some 3.88 million tonnes (mt) of waste arose in Surrey in 2021. This comprised about 2.7 mt of CD&E waste (78%); 273,000 tonnes of LACW (8%), 480,000 tonnes of C&I waste (14%), and some 33,000 tonnes of hazardous waste (1%).

Figure 4. Waste Arisings in Surrey 2021

Figure 4 shows the waste arisings in Surrey in 2021 by waste streams. As shown in figure 4 CD&E Waste makes up the largest proportion of total waste arisings followed by C&I Waste, LACW and Hazardous waste.

Surrey needs to take responsibility for the management of its own waste (the polluter pays principle) in the interests of securing best environmental outcomes including in relation to climate change. Consequently, SCC, as the Minerals and Waste Planning Authority (MWPA), is tasked with identifying opportunities to meet the equivalent needs of the county for the sustainable management of its waste and ensure that it is net self-sufficient in this regard.

In seeking to meet these requirements, amongst others, the MWPA must drive the management of waste up the waste hierarchy, consider the extent to which existing waste management facilities meet the needs of the county, and plan for additional waste management facilities to address any identified capacity gaps.

Waste routinely crosses administrative boundaries and so there is no expectation that every tonne of waste produced in Surrey ought to be managed within the county. The objective of 'net self-sufficiency' is to ensure that there is sufficient capacity to manage the tonnage of waste equivalent to that arising in the county.

Surrey is technically net self-sufficient in waste management terms. However, it does have a shortfall in other recovery capacity, and a shortfall in capacity for non-inert landfill and CD&E waste is forecast to arise in 2031 and 2029 respectively because waste arisings continue to increase, and several temporary waste management facilities are set to close.

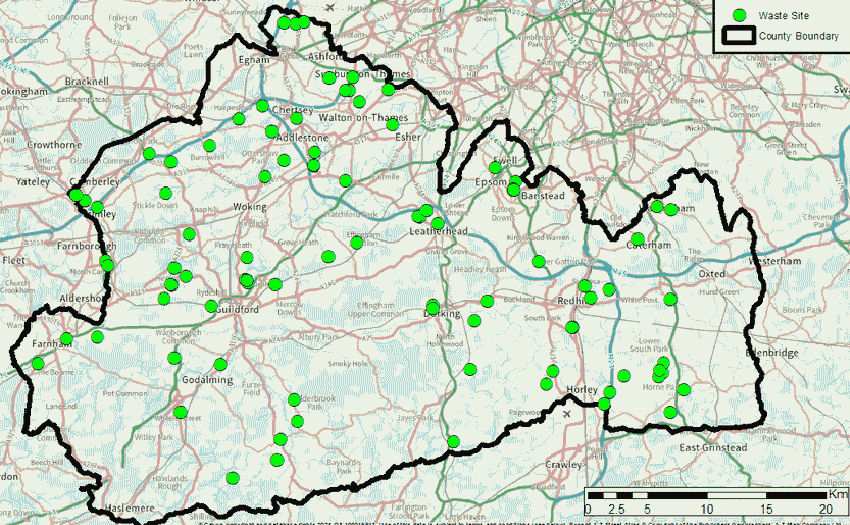

Figure 5: Waste Management Facilities in Surrey

Figure 5 shows the distribution of waste management facilities in Surrey with a high concentration located to the north west, and to the west of the county.

Presently Surrey hosts about 91 operational waste management facilities of varying character which are located throughout the county. A list of existing facilities can be found in Authority Monitoring Reports prepared and published by Surrey County Council (SCC) each year.

Further information about Surrey's waste management capacity can be found on the MWPA's monitoring performance web page.

Planning policy

The National Planning Policy for Waste 2014 (NPPW) explains at paragraph 1 that positive planning plays a role in delivering the country's waste ambitions through a range of mechanisms including:

- Delivery of sustainable development and resource efficiency, including provision of modern infrastructure, local employment opportunities, and wider climate change benefits by driving waste management up the waste hierarchy.

- Ensuring that waste management is considered alongside other spatial planning concerns, such as housing and transport, recognising the positive contribution waste management can make to sustainable communities.

- Helping to secure the reuse, recovery, and disposal of waste without endangering human health and without harming the environment.

- Ensuring the design and layout of new residential and commercial development and other infrastructure complements sustainable waste management.

Paragraph 198 of the National Planning Policy Framework 2024 (NPPF) explains that planning decisions should ensure that new development is appropriate for its location considering the likely effects (including cumulative effects) of pollution on health, living conditions and the natural environment, as well as the potential sensitivity of the site or the wider area to impacts that could arise from the development.

Additionally, paragraph 200 of the NPPF advocates that planning decisions should ensure that new development can be integrated effectively with existing businesses. Existing businesses should not have unreasonable restrictions placed on them because of development permitted after they were established. Where the operation of an existing business could have a significant adverse effect on new development (including changes of use) in its vicinity, the applicant (or 'agent of change') should be required to provide suitable mitigation before the development has been completed.

In this regard, paragraph 8 of the NPPW is clear that when determining planning applications for non-waste development, local planning authorities should, to the extent appropriate to their responsibilities, ensure that the likely impact on existing waste management facilities and on sites and areas allocated for waste management, is acceptable and does not prejudice the implementation of the waste hierarchy and/or the efficient operation of such facilities.

Accordingly, Policy 7 of the Surrey Waste Local Plan 2020 (SWLP) sets out that allocated sites for waste management development, sites in use for waste management including wastewater and sewage treatment works (including those with temporary permission), and sites that benefit from planning permission for waste management (but which have not been developed) are safeguarded.

Policy 7 goes on to explain that proposals for non-waste development in proximity to safeguarded waste management sites must demonstrate that they would not prejudice the operation of the site, including through incorporation of measures to mitigate and reduce their sensitivity to waste operations. Proposals that would lead to loss of waste management capacity, prejudice site operation, or restrict future development of safeguarded sites should not be permitted unless it can be demonstrated by the applicant that either:

- The waste capacity and/or safeguarded site is not required.

- The need for non-waste development overrides the need for safeguarding.

- Equivalent, suitable, and appropriate replacement capacity can be provided elsewhere in advance of the non-waste development.

The SWLP forms part of the Development Plan for Surrey and all planning applications must be determined in accordance with Policy 7 unless material planning considerations indicate otherwise.

Although safeguarding of waste management facilities is a material planning consideration it does not rule out alternative development on or near to land used for waste management. Whether planning permission should be granted for non-waste development is usually a decision for the relevant borough or district council to take, in consultation with the MWPA, and will depend on the circumstances of each individual case. Nevertheless, there is a presumption against development that is likely to prejudice the operation of existing waste management facilities, planned waste management development, or waste management capacity. Sites with temporary consent for waste management are safeguarded for the duration of that consent.

Planning Consultations

To ensure robust waste safeguarding, and in turn sufficient waste management capacity in the county, local planning authorities are expected to consult the MWPA about any proposals for non-waste development near (within about 250 metres) safeguarded sites. This consultation process is set out in the Minerals and Waste Consultation Protocol agreed by Surrey's Local Planning Authorities and published in 2022.

The boundaries of existing waste management facilities and Waste Consultation Areas (250 metres from site boundaries) are identified on SCC's Safeguarding web page and a list of waste management facilities is also published each year as part of SCC's Authority Monitoring Report.

The MWPA welcomes and encourages pre-application discussions with applicants before a planning application is submitted to the MWPA or Local Planning Authorities for determination. Early discussions benefit both applicants and the MWPA by providing insight into any potential safeguarding issues and necessary mitigation thereby streamlining the planning application process. This collaborative approach should help facilitate sustainable development including safeguarding important waste management facilities and capacity. Further information about pre-application advice, including costs can be found on Surrey County Council's pre-application web page.